A BRIEF HISTORY

2 - Studying Art History

The roots of the discipline we practice today emerged during the Renaissance, initially in the context of collecting art, and subsequently in the lecture halls of the art academy. A new technology, the printing press, contributed significantly to these developments in two areas, that of the book and that of the print. Giorgio Vasari, for example, was able to take advantage of the printing press to produce multiple copies of his book of artists' biographies. His book provided both a framework and a methodology for the study of art history.

By the time the first edition of Vasari's Lives was published in 1550, cities in Europe were awash in prints - woodcuts and engravings - that enabled the person in the street to see and possess images of art. A large number of the prints produced at this time are called "reproductive" because they reproduce other works of art, both paintings and sculptures.

For the first time, someone in Antwerp or Paris could see an image of an altarpiece or a fresco in Rome, such this engraving by Cherubino Alberti of part of the Sistine Chapel Ceiling. Prints were actively collected and through them a person could supplement a study of art with reference to examples in distant places. Prints were portable and relatively inexpensive, and could be used also as illustrations in books. During these same years (we are still in the sixteenth century), there also emerged the institution of the art academy, in Florence and Rome, where instruction included studying examples of ancient art, mostly sculpture. However, original examples of antique sculpture were not always available firsthand. Although prints served the need somewhat, the preferred solution was to reproduce the sculpture in the form of a plaster cast. The making of casts of sculpture from plaster of Paris was not a new technology, but it was a technology nonetheless that was utilized by art academies who acquired casts in order to increase the range of examples available to the student. By the 18th century, practically every academy in Europe was in possession of a collection of plaster casts of ancient sculptures. Collections of casts survive in many institutions. Indeed, casts are currently enjoying something of a revival in interest.

Those once in the collection of the University of Oxford have been moved recently into a specially built gallery at the Ashmolean Museum. The cast collection at the University of Austin, Texas, is now housed and exhibited in a museum on campus.

The Crawford Cast Collection in the Crawford Municipal Art Gallery in Cork, Ireland, has a splendid collection of casts of sculptures in the Vatican Museum.

The Pushkin Museum in Moscow has a gallery of casts.

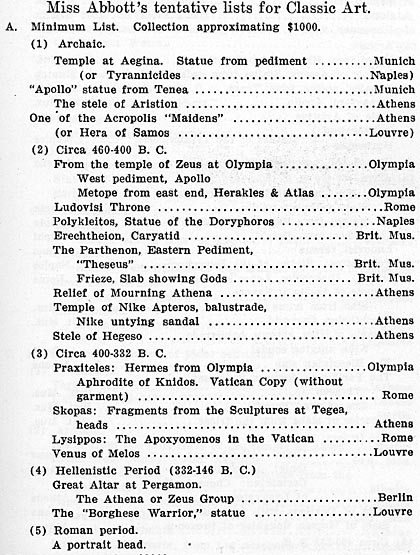

An exhibition of approximately 850 plaster casts of ancient Greek sculpture is on view at the Free University of Berlin. The Berlin collection is the remnants of a cast collection established in 1695 for the Academy of Arts. By 1921 the approximately 2,500 pieces were housed in the Friedrich-Wilhelm University in Unter den Linden where it occupied 24 rooms. It stayed there up until the Second World War during which much was broken or lost. It is difficult for us today to grasp the pervasiveness of the use of casts in the study of art. A report in 1917, titled "On Reproductions for the College Museum and Art Gallery" given by David Robinson of Johns Hopkins University to the College Art Association, and printed in volume 3 of the Art Bulletin, includes lists of casts recommended by Edith R. Abbott of the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

image source: Art Bulletin 3, 1917, 17

Casts could be obtained from the following firms of cast-makers:

It will be noted that the cast-maker August Gerber in Cologne, Germany (mentioned in the caption to the previous image), is not included in this list drawn up in 1917 during the First World War. A minimum list is priced at approximately $1000; a lot of money in 1917. Another longer list is priced at $3000. Miss Abbott explains that "the object is to secure the best working collection for the use of college classes." By 1917, however, the heyday of the plaster cast was over. Casts continued to be used (after all, colleges had spent thousands of dollars on them), but another type of study aid was becoming more popular - the photograph.

|

1

1  2 Studying Art History

2 Studying Art History