A BRIEF HISTORY

5 - Magic Lanterns and Slides

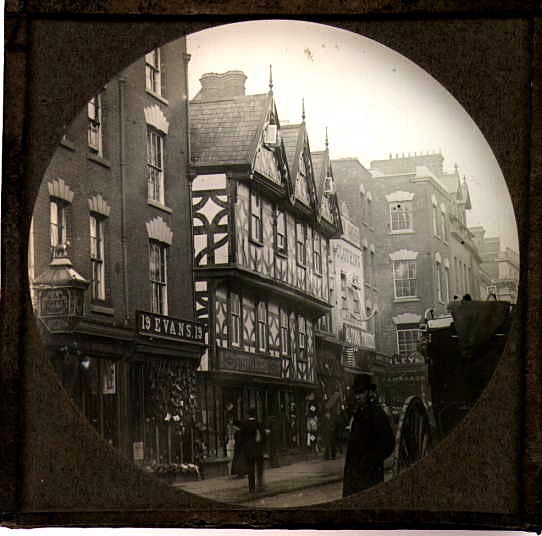

In 1850, two Daguerreotypists in Philadelphia, William and Frederick Langenheim, invented a transparent positive image of a photograph in the form of a glass slide that could be projected onto a wall or screen using a Magic Lantern. The practice of using Magic Lanterns to project images on glass plates was by no means new. As early as the 17th century, glass slides had been projected using a Magic Lantern.

However, the Hyalotype ("hyalo" is Greek for glass), as the Langenheim's called their invention, employed actual photographs. Lantern slides were black-and-white.

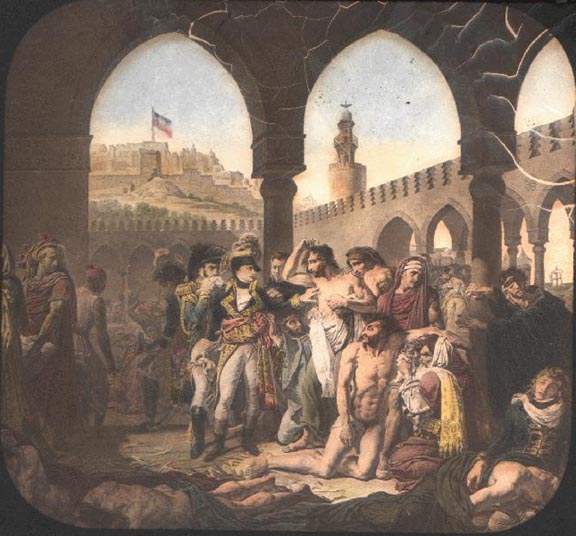

But they were frequently tinted with transparent colours to enhance the effect on the screen, such as in this example showing Gros's painting of Napoleon Bonaparte Visiting the Plague Stricken at Jaffa (March 11, 1799).

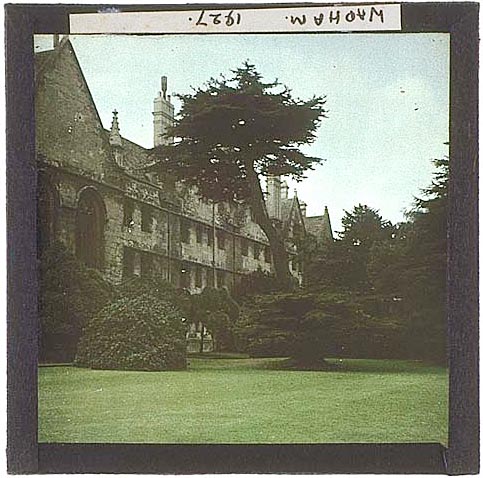

A process for producing colour lantern slides had been invented by the German company Agfa in 1916, but because of the war it did not become available outside Germany until the 1920s. A scan of a lantern slide in Sweet Briar's collection shows the Sphinx and one of the pyramids. As you can see, the Sphinx is still buried up to its neck which means the original photograph must have taken before 1925 when excavations began.

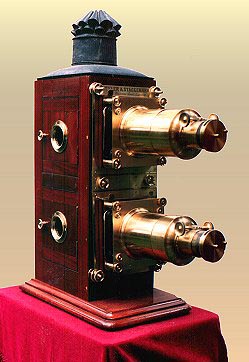

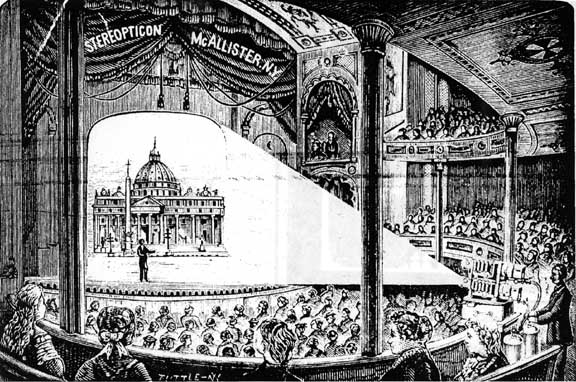

Various types of Magic Lantern projectors were available. There were single-lens projectors but also biunial or double-lens "stereopticon" Magic Lanterns. The biunial projector has two separate optical systems that allow for the projection of dissolves and other effects.

A Biunial or double lens Magic Lantern

Triple lens projectors were also manufactured and could produce even fancier special effects, such as dissolving from one view to another on two of the lenses, while a snow effect is produced from the third. Thus one of the views could be of a scene with no snow, snow then falls and the view dissolves into a view with snow.

In the photograph above on the left we see a "lanternist," as the projectionist was known, standing next to a triunial projector. Beside the projector you can also see a tank of oxygen. By the 1870s, projectors were using limelight as the source of illumination. Limelight is a dazzling white light that was produced by directing a very hot flame onto the surface of a pellet of lime. The earliest and simplest form of limelight was the oxy-calcium lamp. The flame of a spirit lamp was placed near the pellet of lime and a jet of oxygen was used to raise the temperature of the flame and force it against the surface of the lime to produce a brilliant white light. An even brighter limelight could be produced using an oxygen and hydrogen jet.

An illustration from a magic lantern slide catalogue of 1897 shows a large audience attending a slide lecture with an image of St. Peter's Basilica projected onto the screen. If you look carefully, you can see two tanks next to the biunial projector, one for oxygen and the other for hydrogen. The flow of oxygen and hydrogen had to be carefully regulated. These projectors could produce a constant beam of very bright light. A standard 31/4 by 31/4-inch glass slide could fill a screen over twelve feet across. By 1873, Bruno Meyer, a German art historian at the Polytechnic Institute in Karlsruhe, was using projected lantern slides in art history lectures, and actually started to manufacture what he called Glasphotogramme which he sold at two marks a piece. When the new electric Magic Lantern projectors were introduced in 1892, the technology was enthusiastically adopted by Hermann Grimm, a professor of art history at the University of Berlin. In an article published in 1897, he reports how lantern slides permitted the projection of works full-size, or allowed small works or fragments to be enlarged to colossal scale (such as in the the illustration above with an image of St. Peter's Basilica). Grimm's successor at Berlin was Heinrich Wölfflin who also embraced the new technology. He used slides extensively and was the first to use two slide projectors together so he could show details alongside the principal image, or show different images side-by-side.

Projected lantern slides quickly became the favorite technology of the lecturing art historian and remained in use for the next several decades.

As early as 1916, a process for producing colour lantern slides had been invented by the German company Agfa but did not become available outside Germany until the 1920s. In 1936, the discovery of the Kodachrome three-colour process allowed the production of 35mm slides. Beginning in 1938, the transparencies were returned in the now familiar card mounts.

Except for the introduction of colour slides, there has been no major advance in slide technology for the last hundred years.

|

1

1  5 Magic Lanterns and Slides

5 Magic Lanterns and Slides