A BRIEF HISTORY

7 - Digital Technology

Ten years ago, in 1991, I could not have imagined that in 2000 I would be using something called the World Wide Web to show you digital images and text that actually reside on a computer located in some other location. It is safe to assume, therefore, that it is impossible for me to imagine what it will be like ten years from now, in 2011.

As far as it can be judged, we appear to be only at the beginning of a major technological revolution. We are at this point in time like John Ruskin excitedly holding up a Daguerreotype. For him, it was "the most marvelous invention of the century", but he couldn't have imagined then that ahead lay Magic Lantern projectors and glass slides, colour glass slides, 35mm slides, the phenomenon of print photography, moving images, cinematic film, IMAX movies, and even 3-D IMAX movies. So, what can we look forward to?

The new technology has already provided us with a greatly enhanced ability to conduct research and to study artworks. We have ready access through the World Wide Web to library catalogues around the world, to databases filled with data, to huge image resources, to information of all kinds on many thousands of Web sites. Web searches for material for this paper brought forth piles of information from many sources.

Questions that emerge during research and writing can be quickly answered. Bibliography can be easily compiled; images easily tracked down and just as easily downloaded for use. And this is just the beginning. Computer capacities, processing and Internet speeds, data storage, and image quality continue to improve.

For the "special needs" of art historians, digital technology provides a much more precise and accurate way to record visual images. It can achieve a degree of exact mathematical specification impossible to duplicate through the analogue chemistry of photosensitive film emulsions.

If you have been unimpressed with digital images so far, be aware that probably what you have been seeing are not originally digital images; most likely they were images scanned from slides that in turn were photographed from illustrations in books that in turn are reproductions of photographs. Digital images also suffer when viewed through inferior equipment - cheap computer monitors or poor-quality projectors.

The new technology also permits these digital images to be manipulated. This is a tricky issue, I admit, but it is something we need to come to terms with. While we profess our devotion to the "original", the daily tasks of studying and teaching art history are conducted using reproductions. We acknowledge that slides and digital images are representations - they "re-present" the original in ways that change, alter, obscure, or remove completely the colour, scale, lighting, and context.

But whom are we kidding? These same factors have also changed in the hallowed "original". The colours of the Renaissance altarpiece in the museum have deteriorated over time, the lighting is different, and the context is gone. The only thing that survives is scale.

Moreover, slides and digital images reproduce the original as it looks now, or more precisely, as it looked at the time the photograph was taken.

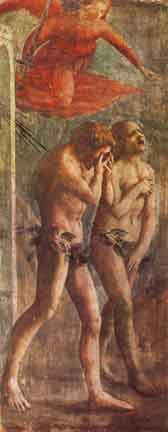

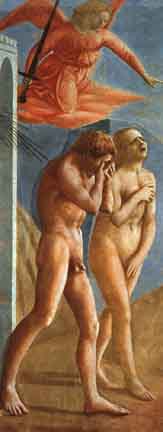

Until a few years ago, this is what Masaccio's Expulsion of Adam and Eve looked like the image on the left. It now looks like the image on the right. Which is the "original"? This is not the place to explore this issue. However, I'll admit that I'm prepared to "improve" an image if necessary, and do other things, such as cropping, or highlighting, or labeling, in order to illustrate one or more of the points or observations I want to make in the classroom. What I want most of all, though, is good-looking image to show my students. As was stated earlier, slides and digital images provide an aesthetic experience that is quite different from that experienced in front of the original. It is, nonetheless, an aesthetic experience for your students, who may never get to see and experience the original. What you can offer in the classroom is a different yet satisfying alternative experience. The new technology already permits us to do things in the classroom we couldn't do before with slides, such as turning a piece of sculpture around, or permit the inclusion of a film clip in the form of QuickTime movie. These examples give us an idea of what we might expect in the future as the ability to do this sort of thing becomes more sophisticated. What will it be like teaching art history in 2011? I predict that the next major phase in the technology revolution will occur in hardware as we discover the real potential of computers and the Internet. Computers will be re-conceived as we discover what they really are. At present they are trapped within a carapace of old technologies: monitors look like television screens, keyboards are like typewriters, material is still organized on "pages." It needn't be like this. I also expect there to be changes in pixel size and configuration that will enable the creation of large digital surfaces, such as walls and ceilings. A "classroom" with "digital walls and ceiling" would not need a projector, the information and images would appear on the surrounding surfaces. It is a short step from that to the replication of complete spaces and environments, such as the interior of the Sistine Chapel, or Chartres Cathedral, or Lascaux, with the additional ability to "move" in any direction; to zoom to any part of that space to examine details close up. Other structures now in ruin can be reconstituted and viewed in a similar manner. By 2011, I imagine it will be possible to simulate three-dimensional objects, such as statues and buildings, in the classroom space. On a vertical digitally surfaced cylinder the image of Michelangelo's David, or Jefferson's Monticello could be viewed from every angle so that it will have a three-dimensional appearance and you can walk around it, or turn it on the screen. Scale could be manipulated and set to "actual size" if desired. This would also apply to other works of art, such as paintings, which it will be possible to reproduce in completely accurate colour. Needless to say, slides will soon be gone; moved into storage alongside the glass lantern slides and the plaster casts. In the meantime, you can scan them if you want, although these images will be inferior to proper high quality digital images. I suggest you scan slides selectively, picking those that are unique photographic records. Lantern slides also record a number of unique images.

This view of the Baptistery in Florence, for example, can never again be photographed in quite this way. But, as you can see here, that old lantern slide can be scanned and digitised using the new technology and the image recovered for use once again in the classroom.

Contrary to the view that technology is somehow a threat to art history, it may be concluded instead that in fact art historians have been successfully using technology all along. Happily, as both a tool and a medium, the new digital technology is especially responsive to the changing needs of art historians today and this bodes well for the future of the discipline.

|

1

1  7 Digital Technology

7 Digital Technology