ARTH232  SPRING 2016 SPRING 2016  SCHEDULE SCHEDULE  REQUIREMENTS REQUIREMENTS

High Classical

c. 450-400 BCE

FREESTANDING SCULPTURE

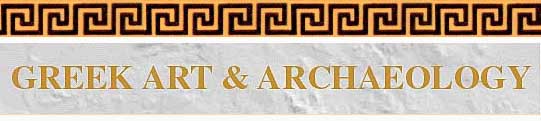

Doryphoros

Imperial Roman marble copy after a lost Greek bronze original by Polykleitos

original, c. 440 BCE

Height 6 feet 11 inches

(National Museum, Naples)

The new contrapposto style is seen more fully developed in this statue of the Doryphoros (Spearbearer) by the sculptor Polykleitos. The figure, which originally held a spear in his left hand, stands like the Kritios Boy. The gradual "S" motion of the body is more pronounced and there is a greater sense of conviction in the body's underlying organic structure - notably the bulging kneecaps, ribcage, and veins in the arms.

The Canon of Polykleitos

Galen (the ancient Greek physician) believed that beauty does not consist in any part particular substance or body but in the commensurate, balanced relationship among the parts of the whole. As an example he mentions the relation of...

"the finger to the finger, and of all the fingers to the metacarpus, and the wrist [carpus], and all of these to the forearm, and of the forearm to the arm, in fact of everything to everything, as is written in the Canon of Polykleitos"

The proportions of the head have changed so that the ears are lower in relation to the eyes, the nose is straighter, and the chin narrower. The head is dome-shaped, as in the Kritios Boy, but the circle of curls has been eliminated and the short, wavy hair lies flat on the surface of the head and face. The Doryphorus is known to be a Roman copy from ancient records indicating that the original was bronze. Typical of Roman copies is the "tree trunk" supporting the back of the right leg, and the block of marble connecting the hip with the right wrist. Since bronze is a stronger medium than marble, it can stand on its own more readily and needs no such additional supports. The use of bronze for large-scale sculpture is another feature of the Classical period Bronze statues were cast using the "lost-wax"

process.

|

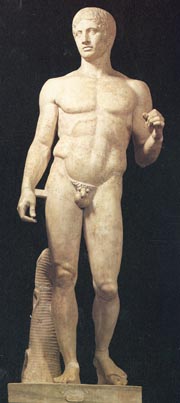

Riace Warrior A

Bronze with copper lips and nipples, silver, and eyes inlaid

c. 460-450 BCE

Height 6 feet 9 inches

(National Museum, Reggio Calabria)

This, and another warrior, were found in the sea off Riace in South Italy in 1972. The figure originally held a shield and a spear. The eyes are of bone and glass paste, while the eyelashes, lips and nipples are of copper. The bared teeth are in silver. The hair has been rendered with the most minute delicacy. The figure exhibits a marked contrapposto stance. The forms of the body show great subtlety of modelling and an amazing naturalism in handling. The figure sways to the right and the left knee advances the front plane. He seems more stylistically advanced, more adventurously engaged in space than the Doryphoros. The figure shows a sophisticated knowledge of muscle, sinew, flesh, bone, cartilage, and of the body in motion. The sculptor understands that the parts of the body are connected, and that movement in one promoted movement in others. Also striking is the exploration of mood. The figure appears energetic and challenging, almost arrogant. There has been much searching through early sources to try and identify the sculptors or workshops who might have made this statue (and its companion). Stimulating theories have been advanced and both statues have been attributed to Phidias himself, but there is no consensus and much speculation.

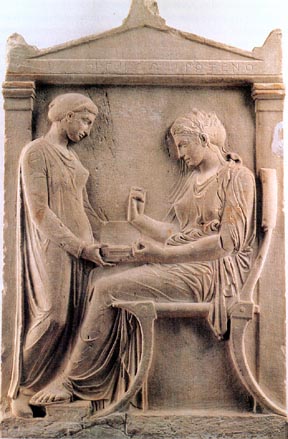

Grave stele of Hegeso

from Athens

c. 400 BCE

Height c. 5 feet 2 inches

(National Museum, Athens)

Graves were often marked by stone monuments - that is, by stone "reminders" or "memorials" - without any overt religious or magic properties. Greek monuments emphasized life rather than death - the memory of the dead in the minds of the living. They were usually upright slabs called stelai carved in relief. In the mid- or late fifth century BCE the relief often included two figures

framed by a kind of pedimented porch. The relationship between the figures gives these works a sombre dramatic power.

In this example, a woman (Hegeso) sits in a chair with a curved back and legs, her sandaled foot resting on a small stool with lion-paw feet. A maid or daughter has handed her a jewel box. Her relaxed pose is revealed by the simple garment she wears. The chair and the maid frame the composition, the curve of the chair back reflected in the curve of the maid's body. Mistress and maid connect at the jewel box from which Hegeso has taken a necklace, once rendered in paint; the position of her fingers indicates that she held the necklace with both hands. The slight inclination of the women's heads lends an air of sorrow to this scene of everyday life that recalls the pleasures of a woman who loved pretty things and has left them behind in death. The beauty of the drapery also evokes the theme of adornment. Hegeso's tunic of nearly transparent linen clings like a second skin, revealing her breasts and legs. Over the tunic she wears a cloak of some fine material bunched up over her stomach and falling over the side of the chair in beautifully ordered folds. Her hair, dressed in waves, is bound with three ribbons and covered behind with a transparent veil. The two figures are placed within an architectural frame formed by two pilasters supporting a pediment topped with palmettes. Hegeso's name and that of Proxenos, her father, are written in the lintel. This stele once stood in the Kerameikos Cemetery in Athens (a replica stands in its place today).

|

© Christopher L. C. E. Witcombe

|

SPRING 2016

SPRING 2016  SCHEDULE

SCHEDULE  REQUIREMENTS

REQUIREMENTS

SPRING 2016

SPRING 2016  SCHEDULE

SCHEDULE  REQUIREMENTS

REQUIREMENTS