|

ARCHITECTURE and ARCHITECTURAL SCULPTURE

OLYMPIA

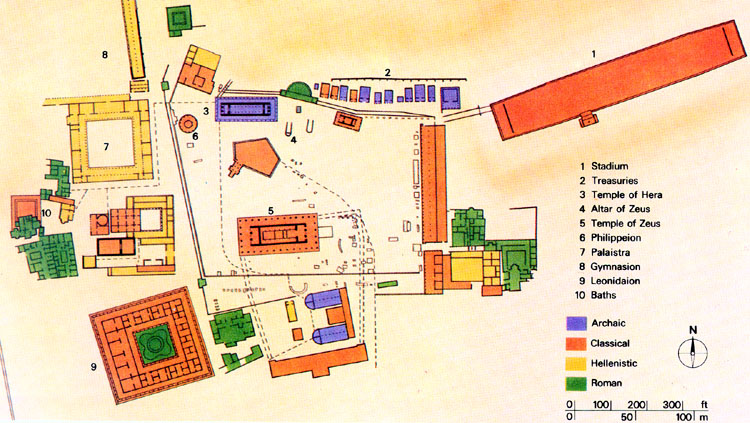

The Sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia contained within its enclosure (called the Altis) the Temple of Hera (wife of Zeus), plus other temples, as well as treasuries and a gymnasium. Olympia also the site of the Olympic Games, initiated in 776 BCE in honour of Zeus. They were the principal athletic meeting of ancient Greece, held in the summer once every four years.

Reconstructed Model of Olympia

Plan of Olympia

THE TEMPLE OF ZEUS

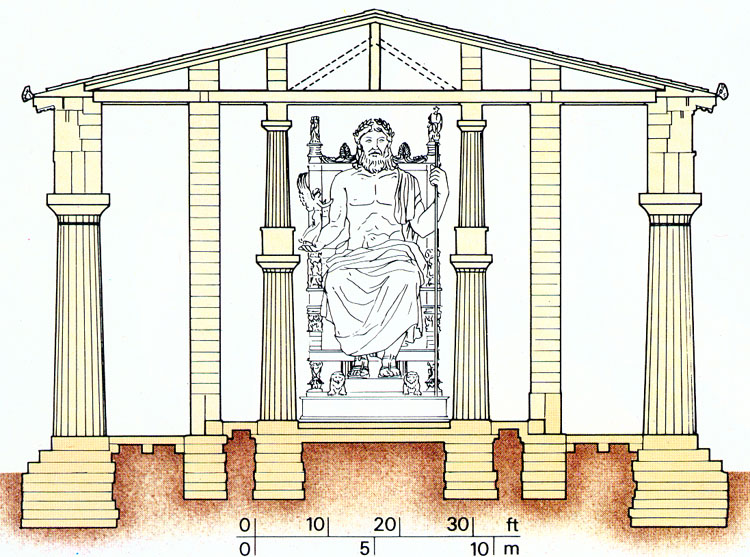

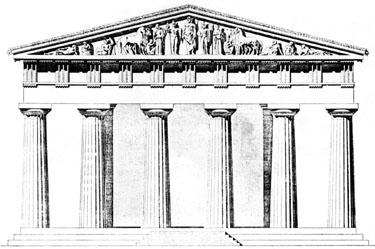

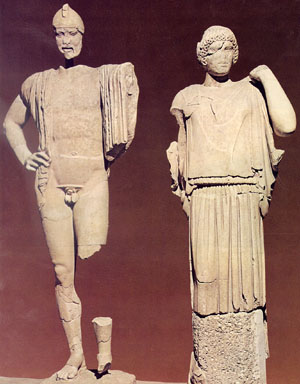

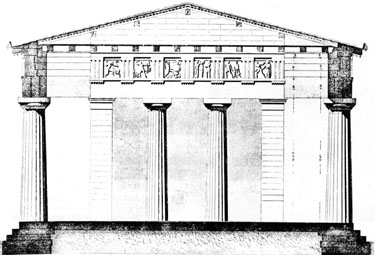

The Temple of Zeus was constructed of a shelly limestone which was originally stuccoed to give the appearance of marble. In comparison with the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina, the exterior Doric columns (6 x 13) are taller and slimmer. The naos had a double-tiered rows of Doric columns.

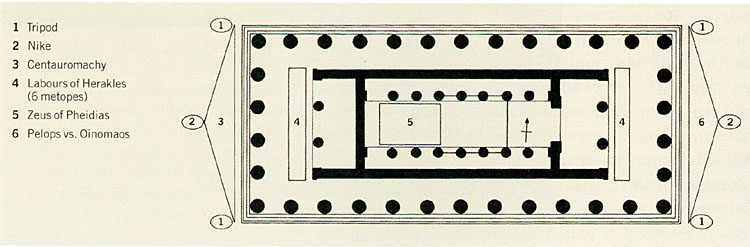

Plan of the Temple of Zeus

with architectural sculpture indicated

The temple was built by a local architect named Libon of Elis. Phidias's colossal chryselephantine (gold and ivory) cult statue of Zeus in the naos was one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

Section through the Temple of Zeus

showing Phidias's chryselephantine cult statue

The pediments (each 80 feet long and 10 feet high in centre) at both ends were decorated with sculptures. The sculptured metopes were placed not on the exterior but in the pronaos and opisthodomos above the columns in antis.

Reconstruction of the East Façade of the Temple of Zeus

The Pediments

The East Pediment faced into the sanctuary and towards the starting line from which the Olympic chariot races began. It represents the story of the chariot race between King Oinomaos and Pelops. Oinomaos had a daughter, Hippodameia, whom he coveted and did not want to lose. Whenever a suitor appeared, Oinomaos would challenge him to a chariot race from Olympia to the isthmus of Corinth. If the suitor, who took Hippodameia on his chariot and was given a head-start, won the race, he also won the bride, but if he was overtaken by Oinomaos, he was killed. Oinomaos, since he had special horses given to him by the god Ares, he never lost and several suitors had been killed.

When Pelops arrived, Hippodameia fell in love with him and persuaded the charioteer, Myrtilos, who was also in love with her, to sabotage her father's chariot by replacing the metal linchpins with pins made of wax. In the ensuing race, Oinomaos's chariot collapsed and he was killed. Later Myrtilos, perhaps in expectation of a reward, made amorous advances towards Hippodomeia, whereupon Pelops threw him into the sea where he drowned, but not before calling down a curse on the house of Pelops.

Reconstruction of the sculptures on the East Pediment of the Temple of Zeus

Sculptures from the East Pediment of the Temple of Zeus

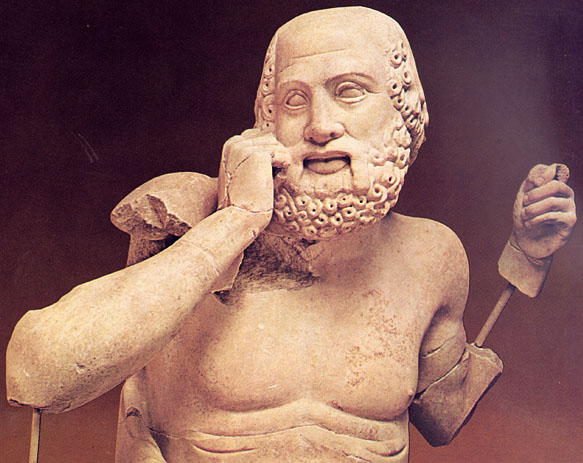

The East Pediment shows the preparation for the chariot race, with the participants offering sacrifice, swearing an oath of fair-play, before Zeus, who stands in the centre between Pelops and Oinomaos. Zeus looks towards his right (one can tell from the neck muscles) at the beardless young Pelops. To the left of Zeus stands the bearded Oinomaos with his mouth slightly open and his brow knit. Next to Oinomaos stands Hippodameia, lifting a veil from her shoulders.

Oinomaos and Hippodamia from the East Pediment of the Temple of Zeus

These central figures are flanked by chariot groups with attendants, and beyond them, two old men. The old men are usually identified as seers. Seer on right displays many new developments. Attention to physical characteristics of an old man - sagging body, bald head. But also given a new dramatic role - projects a clear state of consciousness. His prophetic powers have enabled him to see the consequences of the race and he responds with alarm and concern. An extraordinary attempt at realism.

The seer Iamos from the East Pediment of the Temple of Zeus

The East Pediment as a whole seems like an episode in a great dramatic cycle. As in drama, the violent action takes place off-stage. We are confronted with a scene in which the implications of that action is pondered. There is tension and a variety of conflicting motives driving each of the characters to their fate. They exist is various states of anxiety and knowledge. Oinomaos is violent, guilty of bizarre sins (he is thought to have had an incestuous relationship with his daughter), yet is a victim of betrayal. Hippodomeia, torn between love and duty, has betrayed her father. Pelops, in a sense, is used by Hippodameia. He is the hero, but also the murderer of the man who helped him to victory. The pediment embodies not action, but thought.

Reconstruction of the sculptures on the West Pediment of the Temple of Zeus

The West Pediment is a marked and probably deliberate contrast with the East pediment. It represents the violent action of the Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs, which broke out at the wedding of the hero Peirithoös and his bride Deidemeia.

At the wedding feast, after drinking too much wine, the centaurs attacked and attempted to rape the bride and her handmaidens. A brawl ensued and the centaurs were subdued. The story was selected to express the triumph of human civilisation over the barbaric, animal side of human nature.

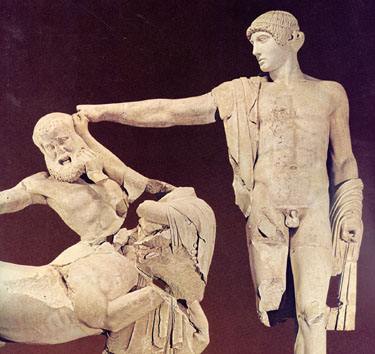

Apollo, Lapith, and Centaur from the West Pediment of the Temple of Zeus

In the centre stands Apollo, who can be understood either as a statue within the scene (i.e. a statue representing a statue), or as an invisible spiritual presence. With a gesture of his right arm, without directly participating in the battle, he seems to be calling the chaos of the scene to order.

Detail of Apollo from the West Pediment of the Temple of Zeus

On either side of Apollo are tangled groups of struggling Lapiths and centaurs. There is a deliberate contrast between the snarling, grimacing centaurs and the self-controlled Lapiths. The West pediment celebrates the triumph of rationality.

The Metopes

Reconstruction showing a cross section at the pronaos entrance of the Temple of Zeus

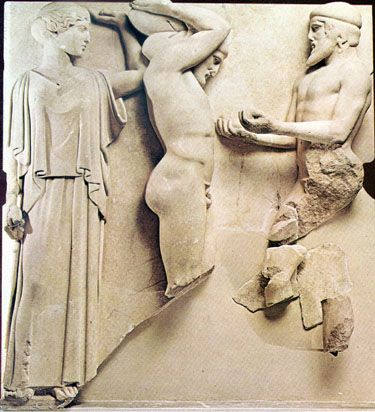

The twelve metopes (six at each end of the building) represent the Labours of Herakles. They exhibit in a highly developed form the distinctive features of the art of the Early Classical period - simplicity of surface, subtlety of expression, and the fusion of ethos ('character' as formed by inheritance, habit, and self-discipline), and pathos (man's spontaneous reaction to experiences in the external world), two forces which the Greeks regarded as forming the root of human emotional exrpession.

In the face of Herakles, who is seen at the beginning of his labours as young, eager, but uncertain (the Nemean Lion); during them as disgusted, wary, or excited (the Augean Stables), and at the end as mature, weary, but triumphant (Atlas and the Apples of Hesperides).

The Golden Apples of the Hesperides brought to Herakles by Atlas

Metope from the East side of the Temple of Zeus

The sculptors seem intent on conveying both what kind of man he is (ethos) and also what he had to endure (pathos). Assisted by Athena in whose face is combined a stern, divine majesty and human sympathy (in Stymphalian Birds metope).

|

SPRING 2016

SPRING 2016  SCHEDULE

SCHEDULE  REQUIREMENTS

REQUIREMENTS

SPRING 2016

SPRING 2016  SCHEDULE

SCHEDULE  REQUIREMENTS

REQUIREMENTS