Present remains of the Great Altar of Zeus, Pergamon

Most of the material excavated by Carl Humann (1839-96) in the late 1870s and early 1880s was transported to Berlin

The approach was from the back, so that only after walking round the building did the great flight of steps leading up to the altar come into view.

Running round the base was a sculptural frieze (only part of which survives) some 7.5 feet high and, in all, more than 300 feet long. (The remains of the building were dismantled after excavation in the late nineteenth century and re-erected in the Berlin Museum in about 1900.)

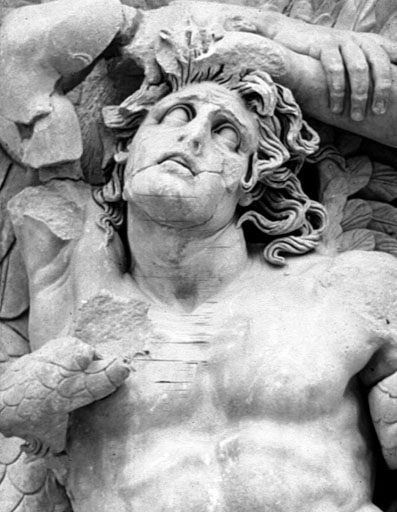

The first and larger frieze is devoted to a battle between gods and giants, the gods being the full height of the relief slabs and the giants even bigger, only their huge menacing torsos being visible. Muscles swell in great hard knots, eyes bulge beneath puckered brows, teeth are clenched in agony. The writhing, overpowering figures seem contorted, stretched, almost racked, into an apparently endless, uncontrolled (in fact, very carefully calculated) variety of strenuous, coiling postures to which the dynamic integration of the whole composition is due. Rhythmic sense is felt very strongly a plastic rhythm so compelling that the individual figures and complex groups are all fused into a single system of correspondences throughout the whole design. Deep cutting and under-cutting produce strong contrasts of light and dark which heighten the drama. The naturalism is extreme and is taken to such lengths that some of the figures break out of their architectural frame altogether and into the spectator's space.

Altar of Zeus, from Pergamon

c. 175 BCE

Marble, reconstructed and restored

(Staatliche Museen, Berlin)

The great frieze shows how the Hellenistic taste for emotion, energetic movement, and exaggerated musculature could be translated into

relief sculpture. In a detail illustrating Athena's destruction of a son of Gaia, the Titan earth goddess, the energy of the juxtaposed

diagonal planes seems barely contained. Athena spreads out both arms, the left bearing her shield.

Athena Battling with Alcyoneus

from the East Frieze, Altar of Zeus, Pergamon

c. 175-150 BCE

Marble, height (of frieze) 7' 7"

(Staatliche Museen, Berlin)

Athena's right hand grasps the luxuriant hair of her adversary Alcyoneus. He is perfectly human except for big wings. Alcyoneus stretches out his left arm in a gesture of supplication, while with his right hand he tries to tear the hand of Athena away from his hair. The long winding strands surround his face like snakes. His features reflect deep anxiety. His mouth is open as if shouting for mercy., the nostrils are dilated, the eyes look up imploringly, full of deep anguish. The eyebrows are drawn, the forehead is wrinkled. His supplication is supported by his mother Ge (or Gaia), the earth, whose upper body appears; both hands are lifted to Athena. Her pleading, however, is in vain. The figure of Nike has appeared at the right to give Athena the crown of victory.

This mythical battle between pre-Greek Giants and Greek Olympians recurs in Hellenistic art partly as a result of renewed threats to Greek supremacy. Unlike the Classical version, however, Pergamon's reveled in melodrama. frenzy, and pathos. King Attalus I defeated the invading Gauls in 238 BCE, making Pergamon a major political power. Later, under the rule of Eumenes II (197 - c. 160 BCE), the monumental altar dedicated to Zeus was built to proclaim the victory of civilization over the barbarians. Greece was trying to reassert its superiority, as Athens had done in building the Parthenon following the Persian Wars. But Hellenistic art, especially in its late phase, reflects the uncertainty and turmoil of the period. By the end of the first century BCE the Romans were in complete control of the Mediterranean world and, with the ascendancy of Augustus in 31 BCE, the scene was set for the beginning of the Roman Empire.

SPRING 2016

SPRING 2016  SCHEDULE

SCHEDULE  REQUIREMENTS

REQUIREMENTS

SPRING 2016

SPRING 2016  SCHEDULE

SCHEDULE  REQUIREMENTS

REQUIREMENTS