|

EXCERPTS FROM: Witcombe, "The Chapel of the Courtesan and the Quarrel of the Magdalens," Art Bulletin, 2002

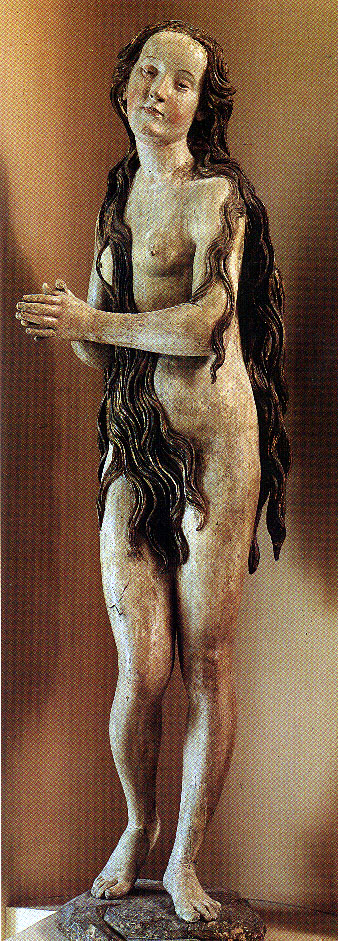

Beginning in the late 15th century, Mary Magdalen's body becomes increasingly eroticized. In the limewood sculpture carved by Tilman Riemenschneider for the Altarpiece of the Magdalen in 1490-92, her head hair cascades down much like that in Botticelli's Birth of Venus to cover only her pubic area. Otherwise, her body is covered in a sort of hairy pelt, except for her head, neck, hands, knees, feet, and breasts, which are left bare.

Mary Magdalen's long hair is apparently derived from Luke's unnamed sinner who evidently had hair long enough to wipe Christ's feet. By the fifteenth century, the vanity of Mary Magdalen before her conversion was seen to focus on her hair. In a sermon given in the early fifteenth century, St. Bernardino of Siena (1380-1444) declared that Mary Magdalen's "third sin was through her hair" which, he adds, "she did everything to make herself more blond" through a practice of "staying in the sun to dry her hair."

Such sermons were aimed at contemporary women. At this time and into the sixteenth century, it was frequently the practice of courtesans to dye their hair blond. The technique of dyeing hair blond was acalled arte biondeggiante. Mary Magdalen's hair is frequently shown blond and is one of her principal attributes.

Her hair was preserved as relics at several locations, such as at S. Lorenzo fuori le Mura and at S. Maria in Trastevere in Rome. Blondness has long been associated with beauty and sex. Botticelli's Venus emerges from the sea to stand like Mary Magdalen wearing nothing but her blond hair.

Tilman Riemenschneider

Mary Magdalen taken up into the air, 1490-92, from the Altarpiece of the Magdalen, from Münnerstadt. Limewood (Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich)

This type of representation can be associated with images of "wild women", such as in Martin Schongauer's more or less contemporary engraving of a Wild Woman.

Martin Schongauer

Wild Woman (engraving), late 15th century

Hairiness of body denoted both sexuality and evil. Animal hairiness, such as in satyrs in ancient mythology, embodied lust, an attribute transferred to the Devil in the Middle Ages. Mary Magdalen's hairiness made her akin to the "wild man" and "wild woman" of the Middle Ages

In the sixteenth century, Johann Geiler von Kaysersberg (Die Emeis ([colophon] Getruckt in der...statt Strassburg von Johannes Grieninger, 1516), established five categories of wild men: solitarii, sacchani, hyspani, piginini, and diaboli. Mary Magdalen was placed among the solitarii, together with Saints Mary of Egypt, Aegidius, and Onuphrius.

Albrecht Dürer

Mary Magdalen taken up into the air, c. 1504-05. Woodcut (214 x 146 mm, 8 3/8 x 5 3/4 in.

Gregor Erhart

Mary Magdalen

Augsburg, c. 1510

polchrome limewood (Louvre, Paris)

|

|

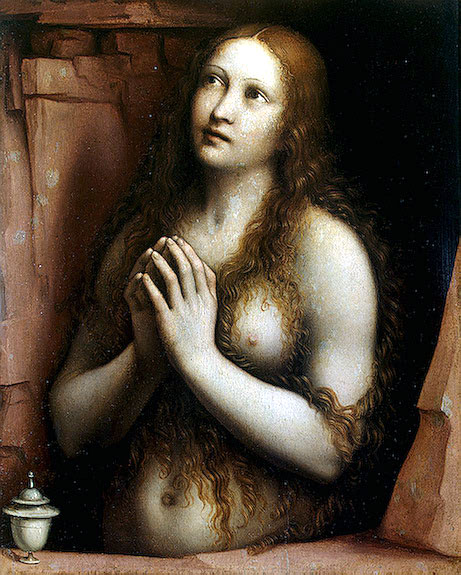

Giampetrino (Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli)

Penitent Mary Magdalen, Oil on panel. 49x39 cm. First half 16th century

(Hermitage, St. Petersburg)

Titian

Penitent Mary Magdalen, c. 1530-35. Oil on canvas, 33 x 27 1/8 in)

Signed (on ointment jar, lower left): TITIANVS (Palazzo Pitti, Florence)

Jules Josef Lefevre

Mary Magdalen in a Grotto, Oil on canvas. 71.5x113.5 cm. 1876

(Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg)

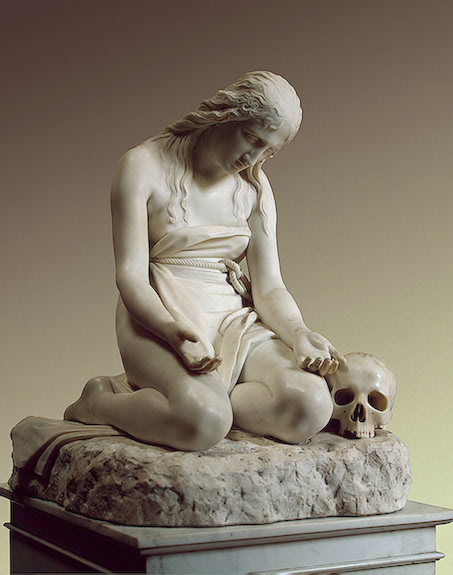

Antonio Canova

Repentant Mary Magdalen, Marble. 1809

(Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg)

|