, the word ‘modern’ was used to refer generically to the contemporaneous; all art is modern at the time it is made. In his Il Libro dell'Arte (translated as ‘The Craftsman’s Handbook’) written in the early 15th century, the Italian writer and painter Cennino Cennini explains that Giotto made painting ‘modern’ [see BIBLIOGRAPHY]. Giorgio Vasari writing in the 16th century, refers to the art of his own period as ‘modern.’ [see BIBLIOGRAPHY]

In the history of art, however, the term ‘modern’ is used to refer to a period dating from roughly the 1860s through the 1970s and describes the style and ideology of art produced during that era. It is this more specific use of modern that is intended when people speak of modern art. The term ‘modernism’ is also used to refer to the art of the modern period. More specifically, ‘modernism’ can be thought of as referring to the philosophy of modern art.

In the title of her 1984 book [see BIBLIOGRAPHY], Suzi Gablik asks ‘Has Modernism Failed?’ What does she mean? Has modernism ‘failed’ simply in the sense of coming to an end? Or does she mean that modernism failed to accomplish something? The presupposition of the latter is that modernism had goals, which it failed to achieve. If so, what were these goals?

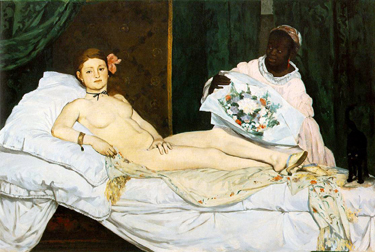

For reasons that will become clear later in this essay, discussions of modernism in art have been couched largely in formal and stylistic terms. Art historians tend to speak of modern painting, for example, as concerned primarily with qualities of colour, shape, and line applied systematically or expressively, and marked over time by an increasing concern with flatness and a declining interest in subject matter. It is generally agreed that modernism in art originated in the 1860s and that the French painter Édouard Manet is the first modernist painter. Paintings such as his Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe (‘Luncheon on the Grass’) and Olympia are seen to have ushered in the era of modernism.

Édouard Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe

1863, oil on canvas (Musée d'Orsay, Paris)

|

Édouard Manet, Olympia

1863, oil on canvas (Musée d'Orsay, Paris)

|

But the question can be posed: Why did Manet paint Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe and Olympia? The standard answer is: Because he was interested in exploring new subject matter, new painterly values, and new spatial relationships.

But there is another more interesting question beyond this: Why was Manet exploring new subject matter, new painterly values and spatial relationships? He produced a modernist painting, yes, but why did he produce such a work?

When Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe was exhibited at the Salon des Refusés in 1863, many people were scandalized not only by the subject matter, which shows two men dressed in contemporary clothes seated casually on the grass in the woods with a nude woman, but also by the unconventional way it was painted. Two years later the public were even more shocked by his painting of Olympia which showed a nude woman, obviously a demi-mondaine, gazing out morally unperturbed at the viewer, and painted in a quick, broad manner contrary to the accepted academic style. Why was Manet painting pictures that he knew would upset people?

It is in trying to answer questions like these that forces us to adopt a much broader perspective on the question of modernism. It is within this larger context that we can discover the underpinnings of the philosophy of modernism and identify its aims and goals. It will also reveal another dimension to the perception of art and the identity of the artist in the modern world.

The roots of modernism lie much deeper in history than the middle of the 19th century. For historians the modern period actually begins in the sixteenth century, initiating what is called the Early Modern Period, which extends up to the 18th century. The intellectual underpinnings of modernism emerge during the Renaissance period when, through the study of the art, poetry, philosophy, and science of ancient Greece and Rome, humanists revived the notion that man, rather than God, is the measure of all things, and promoted through education ideas of citizenship and civic consciousness. The period also gave rise to ‘utopian’ visions of a more perfect society, beginning with Sir Thomas More's Utopia, written in 1516, in which is described a fictional island community with seemingly perfect social, political, legal customs.

In retrospect we can recognize in Renaissance humanism an expression of that modernist confidence in the potential of humans to shape their own individual destinies and the future of the world. Also present is the belief that humans can learn to understand nature and natural forces, and even grasp the nature of the universe.

The modernist thinking which emerged in the Renaissance began to take shape as a larger pattern of thought in the 18th century. Mention may be made first of the so-called ‘Quarrel of the Ancients and Moderns’, a literary and artistic dispute that dominated European intellectual life at the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century. The crux was the issue of whether Moderns (i.e. contemporary writers and artists) were now morally and artistically superior to the Ancients (i.e. writers and artists of ancient Greece and Rome). Introduced first in France in 1687 by Charles Perrault, who supported the Moderns, the discussion was taken up in England where it was satirized as The Battle of the Books by Jonathan Swift.

It was also satirized by William Hogarth in a print called The Battle of the Pictures, which shows paintings mostly by Renaissance and Baroque masters attacking Hogarth’s own works of equivalent but more contemporary subject matter: an Old Master painting of a Penitent Mary Magdalen, for example, attacks scene three from Hogarth’s series The Harlot’s Progress, while an ancient Feast of the Gods attacks scene three from Hogarth’s The Rake’s Progress. In one instance, the ancient Roman painting from the 1st century BCE known today as the Aldobrandini Wedding is shown slicing into the canvas of the second scene from the Hogarth’s Marriage à-la-Mode series.

William Hogarth, The Battle of the Pictures, engraving and etching, 1743

|

Though treated humorously by Swift and Hogarth, the ‘Quarrel of the Ancients and Moderns’ was driven by deeper concerns that pitted institutionalized Authority, whose claim to power was supported by established tradition, custom, law, and lineage, against more progressive individuals who chafed under the restrictions that Authority imposed on their lives and the functioning of society. The conflict introduces an important dichotomy that was to remain fundamental to the modernist question: the division between conservative forces, who tended to support the argument for the Ancients, and the more progressive forces who sided with the Moderns.

In the 18th century, the Enlightenment saw the intellectual maturation of the humanist belief in reason as the primary guiding principle in the affairs of humans. Through reason the mind achieved enlightenment, and for the enlightened mind, a whole new and exciting world opened up.

The Enlightenment was an intellectual movement for which the most immediate stimulus was the so-called Scientific Revolution of the 16th and 17th-centuries when men like Johannes Kepler, Galileo Galilei, and Isaac Newton, through the application of reason to the study of the natural world and the heavens had made spectacular scientific discoveries in which were revealed various scientific truths.

More often than not, these new-found truths flew in the face of conventional beliefs, especially those held by the Church. For example, contrary to what the Church had maintained for centuries, the ‘truth’ was that the Earth revolved around the sun. The idea that ‘truth’ could be discovered through the application of reason based on study was tremendously exciting.

The open-minded 18th-century thinker believed that virtually everything could be submitted to reason: tradition, customs, morals, even art. But, more than this, it was felt that the ‘truth’ revealed thereby could be applied in the political and social spheres to ‘correct’ problems and ‘improve’ the political and social condition of humankind. This kind of thinking quickly gave rise to the exciting possibility of creating a new and better society.

The ‘truth’ discovered through reason would free people from the shackles of corrupt institutions such as the Church and the monarchy whose misguided traditional thinking and old ideas had kept people subjugated in ignorance and superstition. The concept of freedom became central to the vision of a new society. Through truth and freedom, the world would be made into a better place.

Progressive 18th-century thinkers believed that the lot of humankind would be greatly improved through the process of enlightenment, from being shown the truth. With reason and truth in hand, the individual would no longer be at the mercy of religious and secular authorities, which had constructed their own truths and manipulated them to their own self-serving ends. At the root of this thinking is the belief in the perfectibility of humankind.

Enlightenment thinking pictured the human race as striving towards universal moral and intellectual self-realization. It was believed that reason allowed access to truth, and knowledge of the truth would better humankind. The vision that began to take shape in the 18th century was of a new world, a better world. In 1762, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in his Inquiry into the Nature of the Social Contract, proposed that a new social system should rest on ‘an equality that is moral and legitimate, and that men, who may be unequal in strength or intelligence, become every one equal by convention and legal right.’ By joining together into civil society through the social contract, individuals could both preserve themselves and attain freedom. These tenets were fundamental to the notion of modernism.

Such declarations in support of liberty and equality were not only found in books. In the 18th century, two major attempts were made to put these ideas into practice. Such ideas, of course, were not popular with conservative and traditional elements, and their resistance had to be overcome in both cases through bloody revolution.

The first great experiment in creating a new and better society was undertaken in what was literally the new world and the new ideals were first expressed in the Declaration of Independence of the newly founded United States in 1776. It is Enlightenment thinking that informs such phrases as ‘we hold these truths to be self-evident’ and which underpins the notion ‘that all men are created equal.’ The document’s worldly character is reflected in its stated concern for man's right to pursue happiness in his lifetime, which signals a shift away from a God-centered, Christian concentration on the afterlife to one focused on the individual and the quality of a person’s life. Fundamental, too, is the notion of freedom; liberty was declared one of man's inalienable rights.

In 1789, another bloody revolution undertaken in France also attempted to create a new society. Its aim was to supplant an oppressive governmental structure centered around an absolute monarchy, an aristocracy with feudal privileges, and a powerful Catholic clergy, with new Enlightenment principles of citizenship, nationalism, and inalienable rights; the revolutionaries rallied to the cry of equality, fraternity, and liberty.

The French Revolution, however, failed to bring about a radically new society in France. Several changes of regime quickly followed culminating in Napoleon’s military dictatorship, the establishment of the Napoleonic Empire, and finally the restoration of the monarchy in 1814. Revolutionary activity continued, though, in 1830 and again in 1848. Mention can be made here of a third major attempt to create a new society along fundamentally Enlightenment lines that took place at the beginning of the 20th century. The Russian Revolution, initiated in 1915, perhaps the most idealistic and utopian of all, also failed.

It is in the ideals of the Enlightenment that the roots of Modernism, and the new role of art and the artist, are to be found. Simply put, the overarching goal of Modernism, of modern art, has been the creation of a better society.

What were the means by which this goal was to be reached? If the desire of the 18th century was to produce a better society, how was this to be brought about? How does one go about perfecting humankind and creating a better world?

As we have seen, it was the 18th-century belief that only the enlightened mind can find truth; both enlightenment and truth were discovered through the application of reason to knowledge, a process that also created new knowledge. The individual acquired knowledge and at the same time the means to discover truth in it through proper education and instruction.

Cleansed of the corruptions of religious and political ideology by open-minded reason, education brings us the truth, or shows us how to reach the truth. Education enlightens us and makes us better people. Educated, enlightened people will form the foundations of the new society, a society which they will create through their own efforts.

Until recently, this concept of the role of education has remained fundamental to western modernist thinking. Enlightened thinkers, and here might be mentioned for example Thomas Jefferson, constantly pursued knowledge, sifting out the truth by subjecting all they learned to reasoned analysis. Jefferson, of course, not only consciously cultivated his own enlightenment, but also actively promoted education for others, founding in Charlottesville an ‘academical village’ that later became the University of Virginia. He believed that the search for truth should be conducted without prejudice, and, mindful of the Enlightenment suspicion of the Church, deliberately did not include a campus chapel in his plans. The Church and its narrow-minded influences, he felt, should be kept separate not only from the State, but also from education.

Jefferson, like many other Enlightenment thinkers, saw a clear role for art and architecture. Art and architecture could serve in this process of enlightenment education by providing examples of those qualities and virtues that it was felt should guide the enlightened mind.

In the latter half of the 18th century, the model for the ideals of the new society was the world of ancient Rome and Greece. The Athens of Pericles and Rome of the Republican period offered fine examples of emerging democratic principles in government, and of heroism and virtuous action, self-sacrifice and civic dedication in the behaviour of their citizens.

It was believed, in fact, certainly according to the ‘ancients’ in the Quarrel of the Ancients and Moderns mentioned earlier, that the ancient world had achieved a kind of perfection, an ideal that came close to the Enlightenment understanding of truth. The German art historian Johann Winckelmann, writing in the 18th century, was convinced that the art of ancient Greece was the most perfect and directed contemporary artists to examples such as the Apollo Belvedere.

Apollo Belvedere

Roman marble copy after a bronze original of c. 330 BCE (Musei Vaticani, Rome)

|

It is under these circumstances that Jacques-Louis David came to paint the classicizing and didactic historical painting Oath of the Horatii exhibited at the Salon in 1785. David favored the classical and academic traditions both in terms of style and subject matter. His painting depicts a stirring moment in the heroic story of courage and patriotic self-sacrifice in pre-Republican Rome. The firmly modeled statuesque male figures on the left enact a virile drama through which are displayed their noble virtues. The energy and physical tension of their actions is contrasted to the curvilinear shapes and collapsing forms of the women on the right who are shown overcome by emotion and sorrow, showing the weakness of female nature. This was a grand and edifying work treating an honorable and moralizing subject.

Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii

1785, oil on canvas (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

|

David himself saw the role of art in building a new society in no uncertain terms. An active supporter of the French Revolution, he was a member of the Revolutionary Committee on Public Instruction where he explained that the Committee:

considered the arts in all respects by which they should help spread the progress of the human spirit, to propagate and transmit to posterity the striking example of the sublime efforts of an immense people, guided by reason and philosophy, restoring to earth the reign of liberty, equality, and law.

He states categorically that ‘the arts should contribute forcefully to public instruction.’

With respect to the quarrel of the Ancients and Moderns, David can be associated with the supporters of the Ancients. He envisioned a new society based on conservative ideals. In contrast, there were other artists, we can call them Moderns, whose vision of a new world order was more progressive.

The Moderns envisioned a world conceived anew, not one that merely imitated ancient models. The problem for the Moderns, however, was that their new world was something of an unknown quantity. The nature of ‘truth’ was problematical from the outset, and their dilemma over the nature of humans who possessed not only a rational mind open to reason but also an emotional life which had to be taken into account.

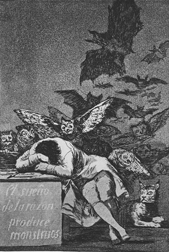

It was also felt that reason stifled imagination, and without imagination no progress would be made. Reason alone was inhuman, but imagination without reason ‘produces monsters‘ (see Francisco de Goya‘s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters). It was agreed, though, that freedom was central and was to be pursued through the very exercise of freedom in the contemporary world.

Francisco de Goya, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters

Etching and aquatint

(Caprichos no. 43: El sueño de la razón produce monstruos), 1796-1797

|

After the Revolution of 1789, the Ancients came to be identified with the old order, the ancien régime. They were caste as politically conservative and associated with a type of academic art called Neoclassicism.

In contrast, the Moderns were seen as politically progressive in a left-wing, revolutionary sense and associated with the anti-academic movement called Romanticism. The nature of this division is best seen in the rivalry of the classicizing artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and the Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix.

In the Salon exhibition of 1824, Ingres exhibited his Vow of Louis XIII and Delacroix his Massacre of Scios. In his review of the exhibition in the Journal des débats, the critic Étienne-Jean Delécluze described Ingres’ work as ‘le beau’ (the beautiful) because in both style and subject matter it followed classical academic theory and promoted the right-wing, conservative values of the ancien régime. In contrast, Delacroix’s painting was labeled ‘le laid’ (the ugly) because of the way it was painted, with loose brushwork and unidealized figures, and because its subject matter, the slaughter of thousands of Greek inhabitants on the island of Chios by Turkish troops in 1822, not only lacked examples of valour and virtue, but also expressed a more liberal criticism of the event and moral outrage over its occurrence in the contemporary world.

J-A-D Ingres, Vow of Louis XIII

1824, oil on canvas (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

|

Eugène Delacroix, Massacre at Chios

1824, oil on canvas (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

|

For conservatives, Ingres represented order, traditional values, and the good old days of the ancien régime. Political progressives saw Delacroix as the representative of contemporary or modern life. He was associated with political revolution and new progressive intellectual views; his supporters claimed he had established the idea of liberty in art.

Delacroix was the first major progressive modernist artist in France. His paintings deliberately rejected the Academic ideal of the beautiful and instead, in the view of conservatives critical of his work, he instituted the ‘cult of ugliness’. Other artists were seen to adopt this same position, notably Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet, each of whom deliberately rejected the Academic model of the beautiful. Their ideas and approach to art were regarded as so subversive that they were accused of attempting to undermine not only the Academy but even the State.

The threat of progressive modernism was such that the State, beginning with the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1855, embarked on a program the effect of which was to neutralize and depoliticize works of art. The plan for the Universal Exposition was to include, in a retrospective exhibition, examples of various different styles of French art, including those of Ingres and Delacroix, in a way that highlighted eclecticism but which simultaneously also had the effect of turning the paintings into non-threatening ‘works of art’. With the support of conservative forces and compliance of formalist critics and art historians, the political and social commentary essential to progressive modernist art was effectively stripped away leaving only the paint on the canvas, which was discussed simply in terms of its formal qualities.

In his guide to the Universal Exposition (Guide pratique et complet à l'Exposition universelle de 1855), Prince Napoléon-Joseph-Charles-Paul Bonaparte, who presided over the Universal Exposition, wrote that in Delacroix’s painting Liberty Leading the People, 28 July 1830 :

There are no longer any violent discussions, inflammatory opinions about art, and in Delacroix the colorist one no longer recognizes the flaming revolutionary whom an immature School set in opposition to Ingres. Each artist today occupies his legitimate place. The 1855 Exposition has done well to elevate Delacroix; his works, judged in so many different ways, have now been reviewed, studied, admired, like all works marked by genius. [Translation from Patricia Mainardi: see BIBLIOGRAPHY]

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People, 28 July 1830

1830, Oil on canvas (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

|

Thus, Delacroix the ‘flaming revolutionary’ was transformed into Delacroix the ‘colorist.’ Although some progressive artists, such as Gustave Courbet, perhaps sensing how inclusion in the exhibition might compromise their work, refused to participate, the Universal Exposition effectively initiated a way to contain the impulses of progressive modernism and neutralize the threat it posed to the prevailing conservative ethos of society.

Until recently, this has remained a prevailing approach to modernism. The socialist statements so forcefully made by Gustave Courbet in his painting The Stonebreakers, for example, and the sharp political commentary of Édouard Manet in his The Execution of the Emperor Maximilian, 1867, for example, have been generally suppressed and replaced by discussions of the formal qualities of each work.

Gustave Courbet

The Stonebreakers

1849-50, oil on canvas (destroyed)

|

Édouard Manet

Execution of the Emperor Maximilian

1867, oil on canvas (Kunsthalle, Mannheim)

|

But although these discussions may have deliberately repressed its revolutionary and confrontational character, progressive modernism itself, as an ideology and a political movement, remained vital and active.