|

The Artist's Nature (Melancholia) - Creativity

"the madness of poets" (and artists)

In the 16th century, together with a changing notion of art, there emerges a concommitant interest in the nature or personality of the artist

- What sort of person was an artist?

- What was the nature of a person who could be inspired in this way?

The link between creativity and melancholy.

It was Aristotle (Problemata XXX, I) who pondered the following question:

"Why is it that all those who have become eminent in philosophy or politics or poetry or the arts are clearly melancholics...?"

In the ancient world, according to early physiology (developed by Hippocrates), Melancholy was one of the FOUR HUMOURS or fluid substances of the body which determined a person's temperament and features.

The variant mixtures of these humours in different persons determined their "complexions," or "temperaments," their physical and mental qualities, and their dispositions.

The ideal person had the ideally proportioned mixture of the four

A predominance of one produced a person who was sanguine (Latin sanguis - "blood"), phlegmatic, choleric, or melancholic.

Each complexion had specific characteristics, and the words carried much weight that they have since lost: e.g., the choleric man was not only quick to anger but also yellow-faced, lean, hairy, proud, ambitious, revengeful, and shrewd.

By extension, "humour" in the 16th century came to denote an unbalanced mental condition, a mood or unreasonable caprice, or a fixed folly or vice

|

The Four Humours

|

|

HUMOUR

|

TEMPERAMENT

|

QUALITY

|

ELEMENT

|

SEASON

|

PLANET

|

|

1. Blood

|

Sanguine

optimistic, cheerful

jovial

|

Wet / Warm

|

Air

|

Spring

|

Jupiter

|

|

2. Phlegm

mucus

|

Phlegmatic

calm, sluggish

apathetic

|

Wet / Cold

|

Water

|

Winter

|

Venus

|

|

3. Yellow Bile

secreted by the liver

|

Choleric

bad-tempered

irritable, bilious

|

Dry / Warm

|

Fire

|

Summer

|

Mars

|

|

4. Black Bile

secreted by the kidneys

|

Melancholic

sad, dejected

depressed, unhappy

|

Dry / Cold

|

Earth

|

Autumn

|

Saturn

|

|

The Days of the Week

|

|

SATURDAY

|

SUNDAY

|

MONDAY

|

TUESDAY

|

WEDNESDAY

|

THURSDAY

|

FRIDAY

|

|

Saturn's Day

|

Sun's Day

|

Moon's day

|

Tiw's Day

|

Wodin's Day

|

Thor's Day

|

Frija's Day

|

|

Sabbath Day

sabato (It.)

samedi (Fr.) |

Sun Day

domenica (It.)

dimanche (Fr.) |

Moon Day

Luna dies

lunedi (It.)

lundi (Fr.) |

Mar's Day

Martis dies

martedi (It.)

mardi (Fr.) |

Mercury's Day

Mercurii dies

martedi (It.)

mercredi (Fr.) |

Jove's Day

Jovis dies

giovedi (It.)

jeudi (Fr.) |

Venus's Day

Veneris dies

venerdi (It.)

vendredi (Fr.) |

Marsilio Ficino maintained that only the melancholic temperament was capable of Plato's creative enthousiasm

Artists were thought to be "born under Saturn", which made them melancholic

- sensitive

- moody

- eccentric

- solitary

These characteristics were displayed by numerous 16th-century artists.

Dürer, Melencolia I, 1514

Notions of artists as "different"

Artists as moody, alienated, eccentric, individualistic

A contemporarty of Leonardo da Vinci describes him when he was working on the Last Supper:

Leonardo had the habit - I have seen and observed him many times - of going early in the morning and mounting the scaffolding, since the Last Supper is rather high off the ground, and staying there without putting down his brush from dawn to dusk, forgetting to eat and drink, painting all the time. Then, for two, three, or four days he would not touch it and yet he would stay there, sometimes one hour, sometimes two a day, wrapped in contemplation, considering, examining, and judging his own figures. I have also seen him - according to how he was taken by his caprice or whim - leave the Corte Vecchia, where he was working at that superb horse of his in clay - and go at midday, when the sun is at its highest, straight to the church of S. Maria delle Grazie, where, ascending the scaffolding, he took the brush and gave one or two strokes to those figures, and then at once went away again to some other place.

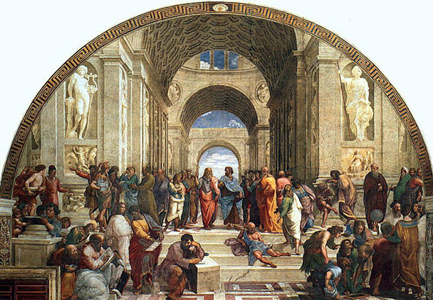

Raphael, School of Athens

Pontormo, Deposition

Vasari describes Pontormo's strange house that the painter had built for himself and which

...had the appearance of an edifice for an eccentric and solitary man rather than of a well-ordered habitation; to reach the room where he used to sleep and at times to work, he had to climb a wooden ladder which, after he had arrived, he would draw up with a pulley so that no one could mount the steps without his wish or knowledge. But what most annoyed other men about him was his own fancy, so that often, when he was sought out by noblemen who desired a work by his hand...he would refuse to serve them - and then he would go and do anything in the world for some low and common fellow at a miserable price.

He was so afraid of death that he could not bear to hear it mentioned, and he fled from the sight of corpses. He never went to festivals, or to any place where people gathered, so as not to be caught in a crowd; and he was solitary beyond belief.

emergence of the notion of individual expression

New interest in drawings

Drawings came to be regarded as closer to original source of inspiration.

If divine inspiration made itself apparent in artists in their behaviour, it may be asked what form it took in the actual art.

Can it be recognized in a work of art?

A word by which 16th century (and later) writers on art seem to have used to identify that extra special something in a work of art was "grazia" (grace)

- Grazia may be thought of as more or less a synonym for a kind of perfect divine beauty

- Very difficult to define - it was a certain "air" - grazia was something added to beauty, but not directly visible (not Alberti's "ornament" added to beauty, which is visible) - a mysterious quality (the source for that feeling you get when you stand in front of a great work of art!)

- Grazia may be assciated with the idea of God-sent inspiration.

- Art (painting, sculpture) was coming to be seen as not merely the product or creation of an artist, but as also containing within it some divine inspiration - a spiritual essence, emanating from God.

- Grazia came to define this something extra - this special quality of divinely-inspired genius.

- Grazia produced the indefinable perfection in a work of art.

- Grazia, however, also defied analysis - it was never clear exactly what it was - it was just there in a great work of art.

- It came to be referred to as "un non so che" - an "I-don't-know-what"

- In 17th-c. France = "je-ne-sais-quoi"

Thus is the 16th century, the products of painters and sculptors came to be seen as possessing something beyond their immediate and merely visible appearance.

A work of art (a term, incidentally, which also appears at this time) was believed to contain an extra indefinable spiritual essence.

It is this which we have come to regard as one of the essential ingredients in our understanding of what constitutes art.

It must be added that this quality came to be described in different terms later on in history.

But it nonetheless remains today an element believed to be essential in a work of art.

It is still regarded as that which in a painting (for example) defined its intrinsic worth (its inward, essential nature) as Art.

It should be added that for centuries only men could be divinely-inspired artists - genius was male.

The belief was that although women could be accomplished as artists, they would forever be unable to transcend their close connection to material Nature and so could never create a masterpiece.

Art (i.e. painting, sculpture and architecture - but not weaving, for example, which was woman's work) - became the domain of men.

Only in recent decades have women been able to break this male monopoly and be taken seriously as artists.

|