|

Proportions

Cennino Cennini, concerning proportions (Book of Art, c. 1437)

- Take note that, before going any further, I will give you the exact proportions of a man. Those of a woman I will disregard, for she does not have any set proportion.

- First, as I have said above, the face is divided into three parts, namely: the forehead, one; the nose, another; and from the nose to the chin, another.

- From the side of the nose through the whole length of the eye, one of these measures.

- From the end of the eye up to the ear, one of these measures.

- From one ear to the other, a face lengthwise, one face. From the chin under the jaw to the base of the throat, one of the three measures.

- The throat, one measure long.

- From the pit of the throat to the top of the shoulder, one face; and so for the other shoulder.

- From the shoulder to the elbow, one face. From the elbow to the joint of the hand, one face and one of the three measures.

- The whole hand, lengthwise, one face.

- From the pit of the throat to that of the chest, or stomach, one face.

- From the stomach to the navel, one face.

- From the navel to the thigh joint, one face.

- From the thigh to the knee, two faces.

- From the knee to the heel of the leg, two faces.

- From the heel to the sole of the foot, one of the three measures.

- The foot, one face long.

- A man is as long as his arms crosswise.

- The arms, including the hands, reach to the middle of the thigh.

- The whole man is eight faces and two of the three measures in length.

- A man has one breast rib less than a woman, on the left side . . .

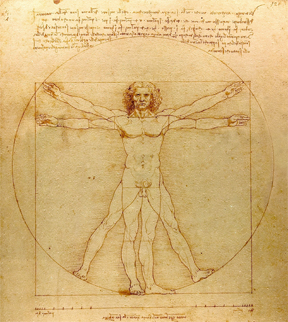

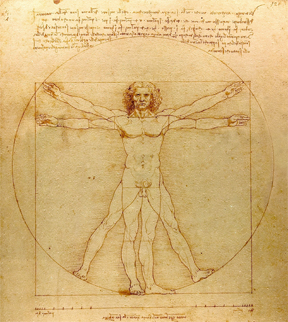

Leonardo da Vinci, excerpt concerning proportions from his Notebooks

- From the chin to the starting of the hair is a tenth part of the figure.

- From the chin to the top of the head is an eighth part.

- And from the chin to the nostrils is a third part of the face.

- And the same from the nostrils to the eyebrows, and from the eyebrows to the starting of the hair.

- If you set your legs so far apart as to take a fourteenth part from your height, and you open and raise your arms until you touch the line of the crown of the head with your middle fingers, you must know that the center of the circle formed by the extremities of the outstretched limbs will be the navel, and the space between the legs will form an equilateral triangle.

- The span of a man's outstretched arms is equal to his height.

Leonardo, Vitruvian Man

drawing (Venice, Accademia)

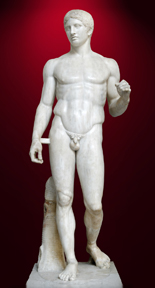

Classical Proportions

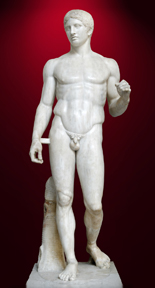

The ancient Greek physician Galen believed that beauty does not consist in any part or particular substance or the human body but in the commensurate, balanced relationship among the parts of the whole. As an example he mentions the relation of

the finger to the finger, and of all the fingers to the metacarpus, and the wrist [carpus], and all of these to the forearm, and of the forearm to the arm, in fact of everything to everything, as is written in the Canon of Polyclitus.

The Canon lays down the proportions of the human body; and the very aim of the Canon was to achieve beauty: beauty itself was conceived as symmetry, as a system of harmonious, balanced proportions.

Doryphoros, c. 450 BCE. Marble

Roman copy after a Greek bronze original by Polyclitus (Height 6'11)

(National Museum, Naples)

Symmetry, and geometrically proportional relationships between parts are certainly visible in 15th century Italian painting:

|

ARTH 341

ARTH 341