Women in the Aegean

Minoan Snake Goddess

Christopher L. C. E. Witcombe

9. Snake Charmers

In 1906, within a few years of Evans's discovery of them, it was suggested that the figurines represent not a goddess and her votaries but snake-charmers brought over from Egypt for the amusement of the palace at Knossos.

While Evans acknowledged that they may be snake charmers, he believed the figures to be the central objects of a religious shrine and so regarded "snake-charming" not as some form of sport or palace entertainment but as a part of their priestly function. Evans does not inquire further into their function, but I suspect that it is in this role, as snake-charming priestesses, that the original purpose and meaning of the figurines may be discovered.

When considered in conjunction with the almost contemporary Egyptian magical objects, it may be suggested that the figurines found by Evans in the Temple Repositories functioned as charms in magical rites performed before shrines, and that, more specifically, these magical rites had to do with the particular concerns of women, among which were fertility, menstruation, conception, and the supply of breast milk.

Fertility, menstruation, and conception were all necessarily connected. The onset of menstruation initiated fertility (the ability to reproduce), which was confirmed through conception. Conception was indicated by the cessation of menstruation. Menstruation was the key and great importance and power was therefore given to menstrual blood.

From the fact that women could conceive only after the onset of menstruation, and that menstruation ceased when pregnant, it was easily concluded that menstrual blood was involved in the creation of life. It is also the case that if a mother breast-feeds her baby, menstruation may not recur for as long as six months, and so menstrual blood was also closely connected with breast milk.

However, as the Greek physician Hippocrates (c. 460 - c. 377 BCE) observed, menstruation caused most women discomfort and some pain. Before the onset of a period, women may experience discomfort in the pelvic area, soreness of the breasts, emotional tension, or tension due to fluid retention in the tissues which also causes bloating.

Moreover, according to Hippocrates, matters could be made worse if menstruation did not take place, for the menstrual blood, rather than being discharged through the vagina, would flow out of the womb and collect in parts of the woman's body causing a variety of illnesses. In particular, Hippocrates regarded accumulated menstrual blood as the cause of potentially life-threatening aberrant behaviour, especially among young virgins whose cervixes had not yet been stimulated to open through sexual intercourse.

These physical and emotional symptoms of what is known today as "premenstrual syndrome" (a term first used by British physician Katharina Dalton in the 1950s), were alleviated as soon as menstruation took place. Besides PMS, cramps, and painfully heavy menstrual flows, women also suffered from irregular periods.

In Egypt, it would appear that spells could be invoked against heavy periods, two of which involved also inserting a knotted cloth (an "Isis-knot"?) into the vagina, while a woman suffering from irregular periods was instructed to recite certain magic words while taking a herbal remedy.

That the figurine of the Minoan "Snake Goddess" might be connected with menstruation is suggested first of all by its colour. In its present condition, the dominant colour of the skirt and the bodice is a darkening golden yellow.

Minoan Snake Goddess

Elizabeth Barber has pointed out that yellow is a woman's colour in the ancient world [see Barber in the BIBLIOGRAPHY]. Yellow dye was obtained from saffron (the dried stigmas of the crocus sativus), a plant which is shown being gathered by women in the Minoan fresco discovered in 1973 decorating the "lustral basin", a cultic room in which it is thought young girls underwent ritual initiations in connection with menstruation and childbirth, in the building named Xeste 3 at Akrotiri on the island of Thera.

Saffron Gatherers

Fresco in the building named Xeste 3, Akrotiri, Thera

Saffron was used medicinally by women to ease menstrual pains. Saffron-gathering is also the subject of a fresco found by Evans at Knossos. As was noted above, saffron-flowers also decorate one of the faïence girdles found with the figurines and also form the central decorative motif on the front of the faïence votive robes (seen hanging on the wall behind the figurines in the photograph of Evans' reconstruction of the shrine).

Snake Goddess Shrine, as reconstructed by Evans

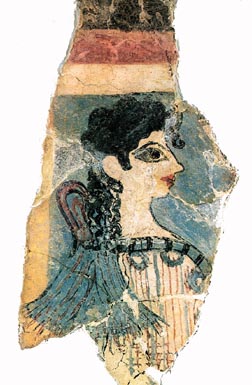

In his description of the votive robes and girdles, Evan's comments, without any explanation of what he means, that the "votive articles of attire find an analogy in the 'Sacral Knot'." Numerous examples of "sacral knots" - a knot with a loop of fabric above and sometimes fringed ends hanging down below - survive in ivory, faïence, or painted in frescoes, or engraved in seals. Evans believed them to be associated with the Mother Goddess. An example would appear to be that worn at the nape of the neck of a Minoan woman in the fresco fragment known as "La Parisienne."

"La Parisienne"

from the Campstool Fresco, Knossos

c. 1400 BCE

(Archaeological Museum, Herakleion)

As Evans notes, a parallel association can be made with the Egyptian ankh. An even better link, however, can be made with the ankh-like symbol tiet which, because of its association with Isis (it represents the goddess's genital organs), is also called the "Isis-knot" and "the blood of Isis."

In the latter case, the reference may be to Isis's menstrual blood. With this meaning, the symbol was often carved on red semi-precious stones such as carnelian, jasper or porphyry, or made from red glass or red porcelain, and served as a protective amulet for women, especially when pregnant. It has been suggested that the Isis-knot originally functioned as a sort of tampon inserted into the vagina of Isis when she was pregnant with Horus to protect the child in the womb from the Seth who wished to destroy it. In this respect, the Isis-knot served to protect against miscarriages.

One of the hieroglyphic signs used to write the word sa, meaning to protect, is a looped cord made of linen thread or leather. It was suggested above that the looped cord projecting above a "knot" between the breasts of both the "Snake Goddess" and the votary may be symbolical. It may in fact represent a magical knot, or sa, to which the Minoan "sacral knot" may be related. The loop of the knot has been identified as a sign of the vulva.

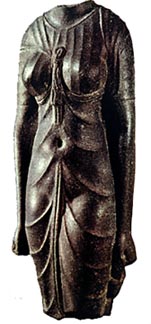

Sa was also the name given to the "the blood of Isis." On statues of Isis, or of women dressed as Isis (such as that from the Ptolomaic period in the Staatlichen Sammlung Ägyptischer Kunst, Munich, below), the Isis-knot is shown between the breasts in the same position it appears on the "Snake Goddess" and on the votary.

Evans's "Snake Goddess"

from Knossos, Crete

c. 1600 BCE

(Archeological Museum, Herakleion)

|

Statue of Isis

(or a woman dressed as Isis)

Ptolomaic period

(Staatlichen Sammlung Ägyptischer Kunst, Munich)

|

Another magical binding device is the belt or girdle. An Egyptian faïence fertility figurine from Western Thebes, dating to the 19th century BCE, wears a girdle made of cowrie shells (long identified with the vulva, cowrie shells are still worn by Muslim women during pregnancy, and are regarded as amulets against the evil eye).

It was noted above that Evans thought that the girdle worn by the votary was perhaps of metal. A 17th-century BCE Egyptian fertility figurine made of clay has a metal ring made of iron fitted tightly around its thighs. It has been suggested that its purpose was to bind the womb closed to prevent miscarriage in a pregnant woman. However, it might also represent what a menstruating woman might describe as an uncomfortably tight band tied around the thighs.

The Minoan figurine "wears" a knotted snake over the region of her womb which might represent the same effect. The knotted snake may therefore have something to do with premenstrual pain or menstrual cramps; both of which might be eased by the loosening of the knot.

Although it is difficult to establish a direct link between snakes and menstruation in Minoan Crete, current anthropology also offers the example of the Australian Aboriginal Rainbow Snake ritual complex in which "menstrual synchrony" is conceptualized as "like a rainbow" and "like a snake."

Some cultures believe that the first onset of menses is caused by copulation with a supernatural snake which also renders the woman fertile and help her conceive children.

From the earliest times, menstrual blood has been associated with creation of life. It issues forth in apparent harmony with the Moon, and when retained by the woman "coagulated" into a baby.

Technically, menstruation is the evacuation from the woman's body of disintegrating tissue that had lined the uterus. In one sense, it is a sloughing off of the old, and when complete, after about five days, the woman and her reproductive ability is renewed. Snakes undergo a similar process of periodic renewal, shedding their old skins and emerging as if reborn.

This constant renewal has made the snake appear ageless to many cultures. The Moon, already intimately linked with a woman's menstrual cycle of (usually) 28 days (the sidereal month, which is the time needed for the Moon to return to the same place against the background of the stars, is 27.321 days), is also associated with renewal and thereby with the snake.

If, as is argued here, the "snake goddess" is a deity devoted to the particular concerns of women, it becomes possible to suggest that the exposed breasts may have some connection with breast milk. A good supply of breast milk was crucial to a baby's survival.

Among the many ex-votos brought to some sanctuaries in Etruscan Italy, for example, were anatomical models of breasts. In Egypt, spells sought to ensure the flow of milk by comparing the breasts of the human mother with those of Isis, or with the udders of Hathor, the Divine Cow.

The two faïence plaques found together with the Minoan figurines showing a cow suckling a calf and a goat (agrimi) suckling a kid may allude to milk-flow. The milk-white colour of the breasts of the "snake goddess" may also draw attention to their purpose.

"Statuette"

from Harbour Town of Knossos

c. 1600 BCE (?)

marble

(Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge)

A marble statuette, of admittedly doubtful authenticity, said to have been found within the area of the Harbour Town of Knossos and now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, shows a women dressed in very much the same way as the faïence "Snake Goddess" with her hands placed on her exposed breasts and holding, or at least touching and covering, the nipples. No snakes are present, but the gesture focusing on the nipples of the breast, and what Evans calls "the maternal aspects," may indicate a connection with lactation.

Attention is again given to the nipples, indicated by little gold studs, of the breasts of the heavily restored ivory figurine in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

"Snake Goddess"

from Knossos

c. 1500 BCE

ivory and gold, 6 1/2 inches

(Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

In each hand the figurine holds a gold snake, which appear to be Egyptian hooded cobras, the body of which is wrapped around the lower arms. She also wears a gold girdle with a small gold strip extending vertically above it representing the fastenings of the bodice, and has five gold bands edging the flounces of her skirt, the upper four being V-shaped in front. Gold armlets on each arm mark the embroidered hems of the short sleeves of the bodice. Evidently, gold bands originally also marked the edge of her bodice, passing around the breasts and up to the sides of the neck. Nail holes indicate that she also wore a necklace, a gold-banded headdress, and had a row of seven gold curls on her forehead.

10. WOMEN IN MINOAN CULTURE

|

Minoan Snake Goddess

from Knossos, Crete

c. 1600 BCE

faïence

height 131/2 inches (34.3 cm)

(Archeological Museum, Herakleion)

Copyright © (text only) 2000

Christopher L. C. E. Witcombe

All rights reserved

|