|

READING

The Eye’s Physical Mechanism

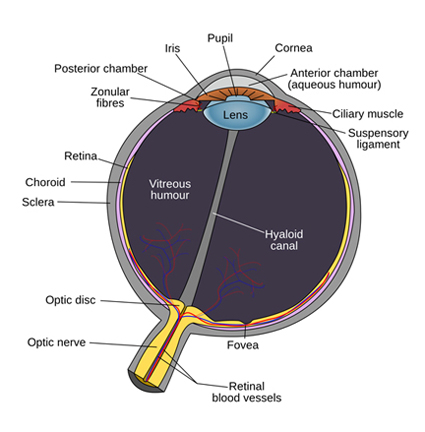

In order for sight or vision to occur, radiation from the electromagnetic spectrum must enter the eye through the pupil and stimulate the photoreceptive rods and cones in the retina. Its path to the retina is controlled by an apparatus of physical parts that fits neatly into a circular opening in the eyeball.

Imagine a hollow sphere about 20 mm in diameter with a circular opening about 12 mm in diameter cut into it. The outer membrane of the eyeball is called the sclera, of which a small part is visible as the ‘white-of-the-eye’. Attached to the sclera around the perimeter of the opening is a dome-shaped, transparent membrane called the cornea.

Visible through the cornea is the iris, which fills most of the opening, and the pupil. The iris is the visible upper portion of the ciliary body, which is primarily a group of muscles anchored around the perimeter of the circular opening. These physical muscles operate the eye’s optical apparatus.

Most of the iris is a single dilator muscle comprising fibers arranged in concentric circles. Functioning in response to various stimuli, the iris will contract, causing the pupil to enlarge (dilate). The pupil is made smaller through the action of the pupillary sphincter muscle attached around the inner edge of the iris.

The opening in the iris never fully closes. The eye is constantly open to the reception of electromagnetic rays. The only way to ‘shut’ the eye is to close the eyelid.

The contraction of the pupillary sphincter muscle can reduce the size of the pupil to as a little as 1.5 mm in diameter. When the dilator muscle contracts, the diameter of the pupil can enlarge up to 9 mm.

In addition to the muscles of the iris, the ciliary body also includes the ciliary muscle. The ciliary muscle is anchored around the perimeter of the circular opening to the choroid, a dark pigmented membrane beneath the sclera.

The primary function of the ciliary muscle is to control the shape of the flexible, transparent lens, which is located directly underneath or behind the iris. As the pupil expands (dilates) and contracts, the iris slides back and forth over the upper (anterior) surface of the lens.

Composed of some 22,000 lamina of transparent fibrous material, the lens is enclosed within a transparent capsule which is attached by an array of non-elastic, hair-like filaments, called the zonules of Zinn, around the capsule’s rim (or ‘equator’) to the encircling ciliary muscle.

The lens is thus suspended in the open centre of the ciliary muscle. Through contraction or relaxation, the ciliary muscle increases or decreases the tension on the zonules, causing them to pull more or less on the lens capsule.

It is generally believed that the ciliary muscle acts like a sphincter so that when it contracts, the central opening becomes smaller. This has the effect of reducing the tension on the zonules, which allows the lens to assume a more spherical shape. Conversely, when the ciliary muscle relaxes the zonules are pulled, and the lens is made flatter and more elongated.

It appears the action of the ciliary muscle also moves the lens forward and backward. When it contracts, the lens is pulled back. This action may occur to prevent the lens pushing against the iris as it becomes more spherical and occupies more horizontal space in the eye.

Conversely, when the ciliary muscle contracts and the lens made flatter, the lens is pulled forward. As shall be seen, both the changing shape of the lens and its movement back and forth alter the eye’s focal length.

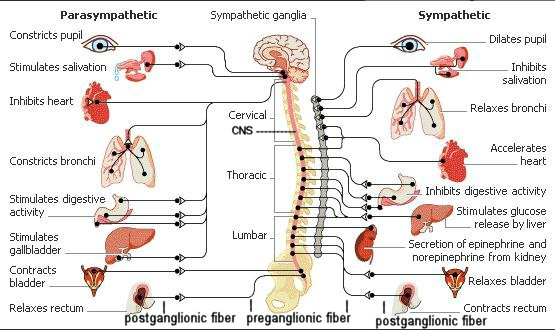

The three internal muscles produce coordinated multiple actions in the eye. Two of the muscles – the pupillary sphincter muscle and the ciliary muscle – are governed by the parasympathetic nervous system.

The pupillary dilator muscle, on the other hand, responds to the promptings of the sympathetic nervous system.

These two nervous systems, working in tandem, form the body’s autonomic nervous system. The autonomic nervous system functions largely below the level of consciousness and governs various internal organs such as the heart, lungs, glands, and eyes. In particular, it governs several important involuntary actions, including:

- diameter of the pupils

- heart rate

- digestion

- respiration rate

- salivation

- perspiration

- micturation (urination)

- sexual arousal

In response to various physical and psychological stimuli, the sympathetic nervous system brings the body into a state of heightened mental and physical alertness.

At the extreme, the sympathetic nervous system prepares the body for possible emergency action, for “flight or fight”. It is also triggered by various sexual stimuli, what might be called the “flirt and mate” response.

Generally, though, it functions in response to the need for increased attentiveness to the visually interesting and the mentally demanding. Once the danger has passed, or interest and attention has waned, the parasympathetic nervous system comes back into play to reverse the changes and return the body functions to a ‘normal’ or default state.

The eye is in a ‘normal’ or default state when both the pupillary sphincter muscle and the ciliary muscle are contracted so that the pupil is relatively small in size and the lens is nearly spherical in shape.

Changes occur when visual and psychological attention is stimulated.

Under these circumstances, the parasympathetic nervous system is overridden by the sympathetic nervous system.

Because the parasympathetic nervous system is no longer operational, both the pupillary sphincter muscle and the ciliary muscle relax.

As the pupillary sphincter muscle relaxes, the dilator muscle of the iris, under the promptings of the sympathetic nervous system, causes the pupil to expand (dilate). As the ciliary muscle relaxes, zonular tension on the lens increases, causing it to become flatter and more elongated.

When the moment of visual and psychological attention has passed, the parasympathetic nervous system resumes control and returns or ‘resets’ the system to its passive or default state: the pupillary sphincter muscle contracts to reduce the size of the pupil and the ciliary muscle contracts to return the lens to its more spherical shape.

However, the eye does not return to a fully relaxed state. Although the eye’s internal muscles may achieve complete contraction, it is unlikely that complete relaxation is possible.

In other words, the eye is always in a state of muscular tension even under non-stimulating conditions. If the ciliary muscle became relaxed to the point that the zonules went slack, the lens would be unstable and subject to the effects of head position and gravitational forces.

The eye’s ‘normal’ or default state in each individual is probably a genetic inheritance from resident ancestors who have already adapted optically to prevailing visual conditions.

However, it is also possible that the eye’s mechanism is calibrated during early infancy, with subsequent minor adjustments made as necessary according to ambient light and visual needs.

Geography (latitude, longitude, altitude, and climate), culture, and gender no doubt also play a role in determining the eye’s ‘normal’ state.

|