|

READING

Illusionism

Illusionism is concerned with creating a direct connection between the forms and space in the image and the spectator's own three-dimensional space. Often this is done in a playful way. One type of image shows someone looking out from an illusionistic space at the spectator producing thereby a sense of continuity between real space and fictive space. Moreover, the action is happening at the moment you look at it, which gives the image a special immediacy and locates it in the viewer's present time.

In a wall fresco painted on a wall by Paolo Veronese, a life-size image of a young girl is seen peering round a partly open door.

The Italian artist Ambrogio Borgognone painted a white-robed Carthusian monk looking down from a real window in the transept of the Certosa at Pavia.

Illusionism can create an impression of objects projecting forward, towards the spectator, and back, away from the spectator. To produce an impression of objects projecting towards the spectator, the artist establishes an artificial picture plane, and then paints objects that seem to project forward from it. In his fresco of the Cumaean Sibyl, Andrea del Castagno painted the architectural frame within which the figure stands so it is perceived as on the plane of the wall's surface.

Then, by painting the sibyl's sleeve, her toes, and the pearl atop her diadem as overlapping this frame, he creates the impression that the forward part of the figure is projecting into the real space in which the spectator stands.

This technique of making objects project forward into the spectator's space was evidently known in the ancient world. The Roman writer Pliny the Elder describes a portrait by Apelles of Alexander the Great holding a thunderbolt in which the Alexander's “fingers have the appearance of projecting from the surface and the thunderbolt seems to stand out from the picture.”

Later, painters used the device to engage the spectator more directly with the image in the painting. In his painting of the Supper at Emmaus, Caravaggio places a basket of fruit in a precarious position on the edge of the table so that it appears to project into our space. If it fell, the impression is that it would fall out of the picture onto the floor at our feet!

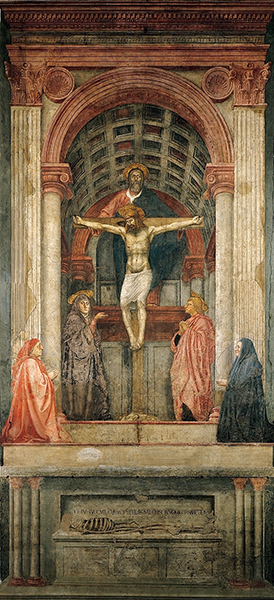

The development of linear perspective during the Renaissance provided some artists with the means to produce human-scale illusionistic images. In his fresco of the Holy Trinity in the nave of S. Maria Novella in Florence, Masaccio utilized perspective to create an illusionistic architectural structure simulating a small chapel or a type of tabernacle.

As in the case of Andrea del Castagno's Cumaean Sibyl, the effect of this type of illusionism is to disrupt our perception of the actual surface of the wall. The fluted pilasters on either side appear to exist in the same three-dimensional space in which the spectator is standing. The perspective projection into the fictive space of the chapel is thus perceived as an extension of our own space.

In effect, Masaccio has made the wall of the church disappear and relaced it with tree-dimensional space occupied by figures. An additional feature of Masaccio's painting is the praying man and woman (the donors) to the left and right appear to be kneeling in front of the chapel, in our space!

This type of illusionism was also applied to ceilings. In the illusionistic oculus (meaning literally an “eye”) painted by Andrea Mantegna, all the orthogonals converge on a vanishing point placed at the centre of the circle. The perspective system allowed Mantegna to calculate the degree of foreshortening both of the winged boy cherubs and the wall against which they stand.

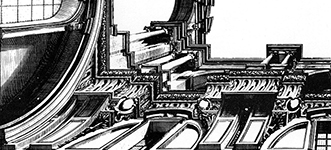

When architecture is foreshortened and painted as an illusionistic extension of the real space of room, it is called quadratura. The technique of quadratura painting was explained by its most accomplished practitioner, Andrea Pozzo, who wrote a book on it 1693.

At this time, Pozzo also painted the nave ceiling of the church of S. Ignazio in Rome employing an elaborate quadratura construction.

An engraving from Pozzo's book gives you some idea of the degree of foreshortening involved in the design for one corner of the vaulted ceiling. The diagonal lines of the architecture follow the orthogonal lines which converge on the vanishing point located in the centre of the ceiling.

The effect attained by Pozzo is that the ceiling has been removed and in its place is an open architectural structure extending vertically up as if from the real walls of the nave. Saints and angels are seen to be carried up on clouds into the light-filled sky above in a tremendous vertical extension of space. An additional challenge for Pozzo was that he also had to take into account the curved surface of the nave vault when he designed the quadratura foreshortening!

In order to view this type of perspectival illusionism, it is necessary to stand in a particular spot, sometimes marked on the floor, where the angle of projection will be correct. When viewed from elsewhere, the painted architecture will appear distorted.

Quadratura illusionism is also applied to walls. On each of the four walls in the so-called Sala delle Prospettive (Room of the Perspectives) in the Villa Farnesina in Rome, Baldassare Peruzzi painted an illusionistic arrangement of columns with views between them into the countryside.

A contemporary example of this type of illusionistic painting could be seen until recently on the south wall of the Fontainebleau Hilton Hotel in Miami Beach, Florida.

The flat surface of the wall between the tower on the left and the building on the right has been painted to give the illusion of an arched opening with a view through it to the sea, sky, and buildings beyond. The reliefs of statues either side of the opening are also painted, as is the architectural design on the left tower.

Perspective can also be employed to create illusionism in architecture. At the Palazzo Spada in Rome, the Italian architect Francesco Borromini and the mathematician Giovanni Maria da Bitonto designed a "perspective gallery" (left). The illusion is that the gallery is the same height and width its entire length. In fact, as in a perspective construction simulating depth, the gallery grows narrower and lower towards the far end. It is also much shorter than it appears to be. So effective is the design in simulating the clues we use to perceive depth, that the degree of illusion is difficult to grasp until a person standing at this end is compared in size with someone standing at the other end (right).

������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

Trompe l'oeil

Trompe l'oeil is a French phrase meaning literally to "trick the eye." It is usually applied to small-scale pictures in which the artist sets out to create real-looking, self-contained image. It relies on a precise and accurate recording of visual detail. An important feature of its effect is the illusion of texture given to each object.

Trompe l'oeil has been admired since ancient times. Pliny the Elder tells the story of Zeuxis painting a picture of grapes that were so realistic birds flew down to them. Proud of his accomplishment, Zeuxis then asked his rival Parrhasius to display his painting by removing the curtain covering it. When he discovered that the curtain was in fact painted, he admitted his defeat, noting that whereas he had deceived birds, Parrhasius had deceived him, an artist.

Trompe l'oeil can be seen in small details in a painting, or it can be the entire painting.

On the lower right side of his painting of the English martyr St. Serapion, the Spanish artist Francisco de Zurbarán included a trompe l'oeil piece of paper with the saint's name on it. The illusion is that it is a real piece of paper attached to the surface of the canvas.

A more elaborate type of trompe l'oeil are paintings composed of several elements, usually arranged against an equally illusionistic background. The trompe l'oeil still-life by the Dutch painter Samuel van Hoogstraten shows a letter-rack stuffed with a variety of mundane objects. It is a type sometimes called a quod libet ("what you will"). Each object is painted with precise verisimilitude, with special attention paid to the texture of each item.

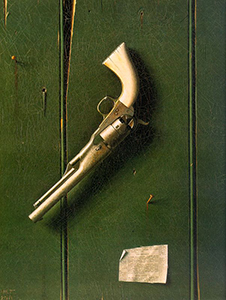

In the United States, where trompe l'oeil painting became popular in the 19th century, the artist William Harnett painted a Colt pistol hanging from its trigger guard on a nail driven into a piece of wood paneling, perhaps the back of a door. A couple of other nails have also been banged into wood which has been damaged and splintered in places. Rust from the nails has stained the chipped paint, and holes where nails have been removed are visible. The pistol shows signs of use and wear in the rust on the barrel and the cracked ivory of the butt. Below is affixed a newspaper clipping with one corner turned up to increase the trompe l'oeil illusion of reality.

|