|

READING

Looking & Associations

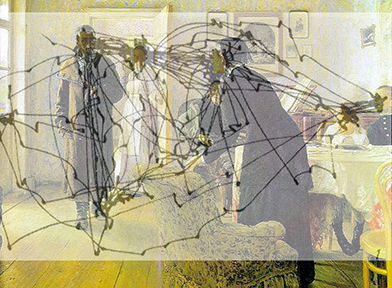

Ilya Repin, The Unexpected Visitor, between 1884 and 1888

In the first moment of seeing Ilya Repin’s painting, The Unexpected Visitor, you also begin looking at it. While seeing is instantaneous, looking takes time. Looking involves the detection and examination of visual features within the image.

You will have noticed in the painting that groups or clusters of lines or configurations of shapes catch your attention, as do contrasting areas of lightness and darkness. Similarly, various colors catch your eye.

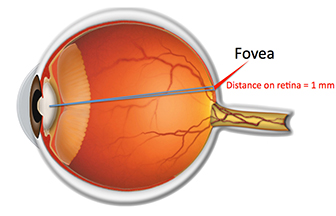

It is these visually interesting features that you now look at. In order to do this, however, your eye must move so that each particular detail is brought in line with the fovea so it can be viewed in sharp focus.

The process of looking involves a series of eye movements executed at high speed.

Contrary to what you may feel to be a steady gaze when viewing an image, the eyes in fact are in continuous motion as they ‘jump’ rapidly from one point of interest to another.

The French term saccade, meaning to jerk or jolt, is used to describe this action. The eye may rest for an average of 180-300 milliseconds on one point and then it jumps at high velocity to another point.

Saccades are the means by which we look at an image. Their purpose is to place this part or that part of an image before the fovea so we can see it clearly.

In a series of experiments conducted in the 1960s, the Russian psychophysicist Alfred Yarbus recorded the eye movements of people looking at Repin’s painting.

Ilya Repin, The Unexpected Visitor, showing eye tracks

A free, undirected examination of the painting by one of Yarbus’s subjects produced a pattern of eye tracks that shows a continuous line tracing the path of the eye as it jumped from one feature to the next.

It is perhaps not surprising to realize that an artist can control these eye movements to some degree through the composition of an image. Through configurations of lines and shapes, arrangements of areas of lightness and darkness, and the placement of color, an artist can compose a picture so that the eyes, rather than jumping randomly around the image, are directed from one point to the next. Indeed, it is the artist’s manipulation of the physical process of looking at a picture that is the basis of composition.

The seventeenth-century French artist Nicolas Poussin composed his landscape painting in such a way that the viewer is visually conducted from one point of interest to the next.

Nicolas Poussin, Funeral of Phocion, 1648

However, in order to look at the painting properly in the way Poussin intended, you must assume an optimal viewing position in front of the original work.

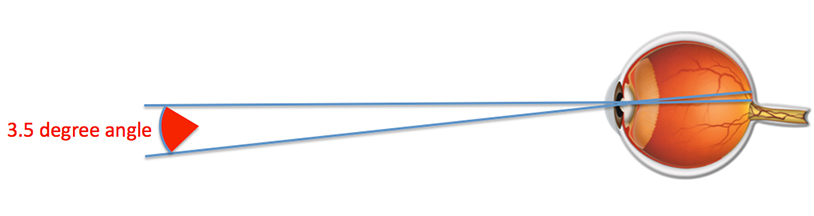

The reason for this has to do with the size of the painting and the size of the fovea. Only a small area of what your eyes are seeing at any given moment is clear and in focus. The angle of vision covered by the fovea is only about 3.5 degrees, which is slightly larger than your thumbnail held at arm’s length.

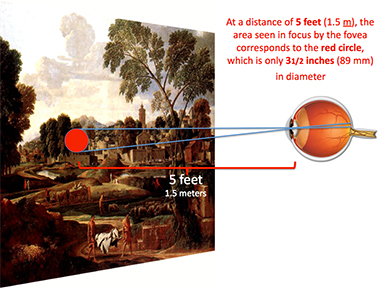

Because of the geometric constancy of foveal vision, your viewing position and the size of the image are very important. When standing five feet (1.5 meters) away from Poussin’s painting, the area that you can ‘look’ at in focus is only about 3.5 inches (89 mm) in diameter.

If you move closer to the painting, the size of this area of focus decreases, and conversely it increases when you stand further away.

There is, therefore, an optimal viewing distance for looking at the original painting. In many cases, especially for works in museums, you can usually choose where you want to stand in front of a painting.

Several factors no doubt contribute to how you make this choice, among them: the size of the painting, the size of features or forms within the painting, and, if present, its perspective system.

Another important factor is the style of the painting. Impressionist paintings, for example, require you to stand at some distance away.

Ultimately, it is the artist who determines for you the best position or location in which to view his or her work. Usually, this involves selecting a point of view that places the painting comfortably within your field of vision.

Only when standing in this optimal viewing position in front of the original work does the painting achieve a proper and satisfying visual coherence. In other words, the composition of the painting makes visual sense only when viewed at the appropriate distance.

This is why viewing the original work is so important! It is only when viewing the original work in the optimal viewing position is its essential visual coherence properly observed.

Photographic reproductions usually distort two vital factors: the size of the original image and your distance from it. You are thus unable to look at a reproduced painting in the way you look at the original.

The act of looking is the means by which we gather visual information.

Each detail is brought into focus by moving your eye to align it with the fovea. A small circular area is seen in focus, while the rest of the painting remains blurred and lacking clear definition.

The reason you look at each detail is because it has caught your visual attention. As you are looking at one detail, your eye may catch sight of another interesting configuration of lines, or shapes, or contrast, or color, and it executes a saccadic jump to look at it in focus.

This happens very fast, with the eye often returning again and again over the same path or following a different route from one detail to another. Both the nature of the detail and the ballistic activity of the eye as it jumps to it are nicely described by the familiar term ‘eye-catching’.

Recognition and Identification

The primary task of looking is recognition and identification.

To recognize is to grasp the image of something you already know. When you again see the same painting by Poussin that you had previously seen, you re-cognize or re-know it.

To identify something is to see that what you are looking at has the same qualities or features as something else you already know. The same process applies when you look at details in an image.

In Poussin’s painting, you were perhaps able to identify the white shape in the foreground as a human body wrapped in a white sheet being carried on a stretcher.

Nicolas Poussin, Funeral of Phocion, 1648

The next detail you looked at, was perhaps the figure with some sheep, and so identified him as a shepherd, and so on.

Your ability to make these identifications depends on the extent of your knowledge and whether or not you can associate what you are looking at with other similar images already known to you.

The process involves evaluating various visual clues. Both the act of recognition and the process of identification involve association and comparison. What you are looking at is associated and compared with the same or similar images stored in your memory.

Associations

Associations are the connections in thought and ideas that you make between what you know and what you see in the image.

Associations may follow an initial impression, although it is also the case that an impression may derive from one or more associations. Unlike impressions, associations are generally more consciously processed, although your initial associative response may be intuitive.

Associations do occur when you first see an image, but they are more directly the result of looking at various details and features. This shift between impression and association can happen so quickly that it is difficult, if not impossible, to know which came first. As you look at features or details in an image, the initial process of association involves recognition or identification.

Jan Van Eyck, Arnolfini Double Portrait, 1434

For example, as you gaze at Jan van Eyck’s painting, you are able to identify the particular arrangement of shapes, lines, colors in the center foreground as a dog because you can associate what you are looking at with an idea or image you already have in your mind of a dog. You may then quickly go on to associate other pieces of information or ideas with this particular detail.

Most representational artworks communicate through associations made with recognizable or identifiable objects or people in the image. Generally, associations are emphasized in images that are realistic.

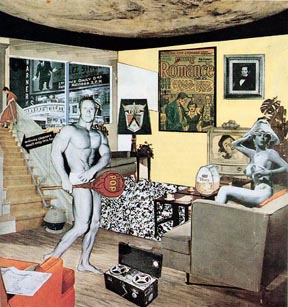

In the twentieth century, the style of art making preferred by some artists stressed associations to the neglect of impressions. For example, the small collage, Just what is it that makes today’s home so different, so appealing? (1956), by the British Pop artist Richard Hamilton, is dominated by the associative significance of each item shown in the image.

Richard Hamilton, Just what is it that makes today’s home so different, so appealing?, 1956

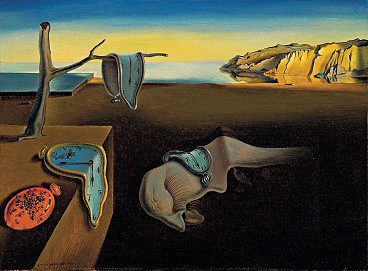

Some artists, such the Surrealist artist Salvador Dalí, provocatively challenged our propensity to make associations by juxtaposing in his paintings, such as his Persistence of Memory, various distorted and oddly disposed objects that confound any immediate associative understanding.

Salvador Dalí, Persistence of Memory, 1931

In a series of photographs, the contemporary photographer Cindy Sherman presents images, ostensibly of film stills, in a way that provokes a familiar pattern of associations but which cannot be resolved. The effect is to place the image’s meaning just beyond the viewer’s grasp.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still No. 21, 1978

Types of Associations

The process of association is a natural and essential part of how humans function in the world. Associations give or add meaning to the image.

The artist Jan van Eyck deliberately placed a dog in his painting in order to induce certain associations in the mind of the viewer. The dog serves as a signifying sign within the painting, telling you something about the man and the woman. The dog may also serve as a symbol. In this instance, Jan van Eyck may have intended the dog to symbolize fidelity or faithfulness, in reference to the couple.

Signs, symbols, and allegory are all types of association and are briefly discussed below.

As already noted, the process of association begins with recognition and identification. The act of recognition and the process of identification involve associating and comparing what you are seeing with the same or similar images stored in your memory. It involves evaluating various visual clues in the image that you find to be consistent with what you already know. In the process, each image that you see also becomes part of your stock of reference images.

The process of association, however, is more than simply recognizing or identifying what you are looking at. In works of art especially, the artist can introduce different types of associations that add to the meaningfulness of the image.

Signs

In a broad sense, a sign is any object or element that is seen in an image that conveys meaning. A sign first signifies what it represents, but it also signifies other things.

The dog painted by Jan van Eyck, for example, represents a dog, but it is also signifies additional meaning when placed in the context of the man and woman.

A sign functions to provoke in your mind a sequence of associations. When this happens, you can say that the object or element is ‘significant’ for you. Everything that an image signifies becomes part of its meaning and influences your interpretation of it.

The word ‘sign’ also reminds us that what we see in an image is not the actual thing - a dog, a man, a woman, a piece of fruit - but an image of it.

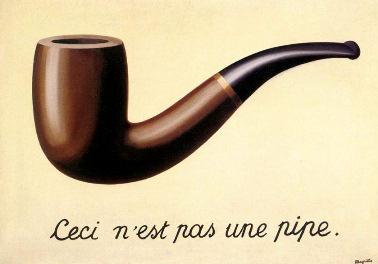

The Belgian artist René Magritte cleverly illustrates this point in his painting La trahison des images (‘The Treachery of Images’).

René Magritte, The Treachery of Images, 1928–29

Although the image portrays a meticulously rendered briar pipe, Magritte includes the words “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (‘This is not a pipe’). Magritte reminds us that what we are seeing is not, in fact, a pipe but an image of a pipe. The pipe in the painting is a ‘sign’ for an actual pipe.

Symbols

A number of signs may also be understood as symbols. A symbol is conventionally understood as something used for or conceived as representing something else. A symbol is a communication element intended to represent or stand for a person, object, group, or idea.

Whereas the meaning of a sign may shift as its context changes, the meaning of a symbol is locked in and remains the same wherever it is placed. Because meaning is already established, symbols limit or confine the process of association.

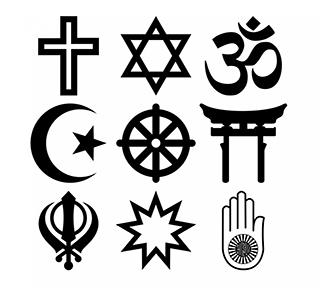

Religious symbols

Symbols may be presented graphically, such as in the cross for Christianity or the national flag of a country.

A graphic symbol may also be a shape, such as a circle, which is regarded as a symbol of perfection.

Symbols can also be representational, as in the human figure of ‘Uncle Sam’ standing for the United States.

Uncle Sam

Symbols can also be letters, such as K for the chemical element potassium, or they may be assigned arbitrarily, as in the symbol $ for dollar.

Symbols may be anything represented in the work of art, such as an object, or an action, or a pattern of objects and actions, or a non-representational item such as a color or a line. For example, various colors have served symbolical functions throughout history.

In ancient Egypt, red symbolized blood and therefore also life. Bright yellow, the color of gold, an everlasting metal, symbolized eternity. Blue represented truth, while green symbolized youth and freshness. White denoted light as well as dawn and the feeling of joy, while the color black was associated with the mysteries of fertility and the afterlife.

For Christians in the Middle Ages and during the Renaissance in Europe, however, these same colors had a different set of symbolical associations.

Red was associated with charity and yellow-gold with dignity. Christians today continue to identify white as the color of purity and black as the color of humility.

Other cultures and religions have their own rich color symbolism.

Besides these individual symbolic items (colors, objects, etc.), a whole image can also function symbolically and represent notions or concepts such as evil, or progress, or courage. Usually when a whole image is functioning symbolically, it is described as an allegory.

Allegory

An allegory is an image that uses symbolic fictional figures (personifications) and actions to convey truths or generalizations about human conduct, actions, or experience.

A personification is the representation of an abstract quality, thing, or object in human form.

In a work of art, allegory is a way of representing other deeper meanings in the guise of a more superficial or literal image. The figures that appear in an allegory may personify, embody, or symbolize moral qualities or abstract ideas or concepts, such as justice or victory. As a type of association, allegory has been employed by numerous artists over the centuries.

Eug¸ne Delacroix’s painting Liberty Leading the People is an allegory of the revolution that took place in France in July 1830.

Eug¸ne Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People, 1830

The central figure is a personification of ‘liberty’ who is shown leading a crowd of armed men over a street barricade. The accompanying figures represent in a symbolical way the different classes involved in the uprising. The tricolor (the three-color flag), the bell towers of Notre-Dame cathedral seen in the distance on the right, and the haze of smoke are also symbols that contribute to the meaning of the allegory, the subject of which is the heroic rebellion of the French populace in the name of liberty against the Bourbon king Charles X.

It is not always obvious when an image is an allegory. A deeper, allegorical meaning may be suspected, however, when the images includes anomalous figures, actions, and objects.

In Delacroix’s painting, for example, it is otherwise unlikely that a tall, barefoot woman with her breasts exposed and wearing a Phrygian cap would be seen leading a group of armed Parisian citizens in 1830.

Similarly, the curiously dressed figure of the artist painting a picture of a woman posed as a personification of Clio, the muse of history, alerts the viewer to the fact that Vermeer’s painting is an allegory, in this case of the art of Painting.

Johannes Vermeer, The Art of Painting, c. 1656

|